A Brief Discussion on Phrases with “的”, “地”, and “得”

Disclaimer: This post was originally written in Chinese and translated into English by GPT-5.2.

- The High Frequency of De “的, 地, 得” Usage

1.1 Without considering differences in written form, De “的, 地, 得” is very likely the word with the most complex part-of-speech behavior in the lexical system of Modern Chinese. Here, “part of speech” refers to the grammatical meanings that a word may produce when it enters a linear segment of language—i.e., when it is used. “Grammatical meaning” in this article is meant in a broad sense: it may refer to syntactic, semantic, or pragmatic meaning, and so on.

1.2 The complexity of part-of-speech behavior is closely related to the frequency of word usage. According to statistics from the online “Modern Chinese Corpus Word Frequency List” (corpus size: 20 million characters), the occurrence frequencies (frequency) of the three words “的, 地, 得” in Modern Chinese are 7.7946%, 0.443%, and 0.1957%, ranking 1st, 14th, and 46th respectively in the “frequency list.” The specific statistics may vary slightly among sources, but “的” is always the highest-frequency word in Modern Chinese, and “地, 得” always follow in rank, remaining near the top of the high-frequency list. In short, De “的, 地, 得” is undoubtedly the most frequently used word in Modern Chinese (8.43333%), far beyond the reach of any other word (the total frequency of the top 11 high-frequency words excluding “的” is 8.4225%, still slightly lower than De “的, 地, 得”). This high frequency of use causes De “的, 地, 得” to carry a large number of functional uses—i.e., “usages” (usage)—which to some extent explains the complexity of De “的, 地, 得” in terms of part-of-speech behavior.

This also suggests that analysis at the pragmatic level or functional level is an indispensable perspective when examining the motivating factors behind the formation of the complex part-of-speech behavior of De “的, 地, 得,” and it deserves great attention.

2. The Complexity of the Part-of-Speech Behavior of De “的, 地, 得”

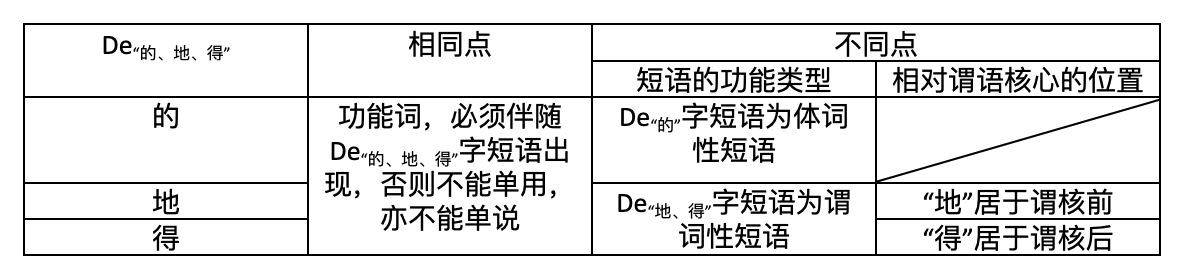

2.1 The complexity of the part-of-speech behavior of De “的, 地, 得” is first manifested in its three variants in written form: 的, 地, 得. The distinction in written form reflects people’s awareness of the complexity of the part-of-speech behavior of De “的, 地, 得.” In other words, people are aware (possibly as a collective unconscious) that in Modern Chinese, De “的, 地, 得,” which share the same phonological form, are internally complex and heterogeneous in terms of part-of-speech behavior, and can be divided into at least three types—namely, De “的,” De “地,” De “得,” or “的, 地, 得”—so people consciously distinguish them in writing. The ideal relationship among the three (the typical relationship in cognition) can be represented as follows:

From the table we can see:

First, without exception, “的, 地, 得” are all function words, or in other words, all empty words; they must be used within De “的, 地, 得”-character phrases, so all their grammatical functions lie in participating in the construction of De “的, 地, 得”-character phrases, and their grammatical meanings can only be manifested within De “的, 地, 得”-character phrases. From this perspective, De “的, 地, 得” can be treated as a single function word as a whole.

Second, the three part-of-speech variants within “的, 地, 得” can be segmented through two steps: Step 1: if the functional type of a De “的, 地, 得”-character phrase is nominal, then “的” can be segmented out of De “的, 地, 得”; if the functional type of a De “的, 地, 得”-character phrase is predicative, and the position of “地/得” is before the predicate core, then “地” can be segmented out; otherwise “得” is segmented out.

2.2 The complexity of the part-of-speech behavior of the three words “的, 地, 得” themselves is also unequal. This is another manifestation of the complexity of the part-of-speech behavior of De “的, 地, 得.”

Obviously, in Modern Chinese, the part-of-speech behavior of “地, 得” is far more singular and stable than that of “的”: “地” is used only in adverbial-middle phrases, “得” is used only in predicate-complement phrases, and both occupy the middle position within the phrase in which they occur (“地” before the predicate core, “得” after the predicate core). By contrast, “的” can appear in the middle to form attributive-middle phrases; it can also appear at the end to form the commonly used “的”-character phrases in the mainstream Modern Chinese system used for reference; and it can also form various kinds of De “的”-character phrases that are structurally equivalent or similar to the two types above but whose grammatical meanings are very different.

In this sense, “的” concentrates the complexity of De “的, 地, 得” in terms of part-of-speech behavior, while “地, 得” have already completely been bleached into grammatical markers of adverbials and complements in Modern Chinese. Although “的” has also completely been bleached into a grammatical marker, the internal nature of this grammatical marker is not simple.

2.3 The inequality of the part-of-speech behavior of the three variants of De “的, 地, 得” is also reflected in people’s spontaneous usage, just as the spontaneous distinction of the three in written form reflects people’s understanding that their parts of speech differ.

First, in terms of word frequency, the occurrence frequencies of “的, 地, 得” in Modern Chinese are 7.7946%, 0.443%, and 0.1957% respectively. The frequency of “的” accounts for about 92.43% of the frequency of De “的, 地, 得,” and is a little more than 12 times the frequency of De “地, 得.” This inequality in usage frequency also to some extent explains the inequality in their part-of-speech complexity.

Second, in actual use, people often mistakenly write “地, 得” as “的,” rather than the other way around. This causes the frequency of “的” to include a portion that actually belongs to the frequency of “地, 得,” resulting in statistical error.

However, due to the lack of relevant research and statistics, we cannot determine to what extent this confusion contributes to the inequality of usage frequencies of “的, 地, 得,” or to what extent it affects the conclusion in 2.3. But what we can be sure of is that even if this confusion exists, it is limited and insufficient to change the fact that “的” is dominant in the usage of De “的, 地, 得,” and insufficient to change all the conclusions above. The discussion below will continue to confirm this. On the contrary, rather than reflecting a complex situation in the usage of a specific De “的, 地, 得” variant, this confusion phenomenon instead reflects the cognitive dilemma people face in the correspondence and conversion between spoken and written language: on the one hand, people can perceive differences among components of the language system or within a component (in sound, meaning, function, etc.), and on this basis develop corresponding written-language conventions and theories of language analysis; but on the other hand, people’s understanding of these differences is logically not strict, not complete, and not thorough, which is also manifested in the imperfections of the corresponding written-language conventions and theories of language analysis. Human cognition has this kind of logical duality, and natural language also has this kind of logical duality; the two should be able to correspond to each other.

Perhaps, the complexity of the part-of-speech behavior of De “的, 地, 得” is merely a small facet of the complexity of the entire Modern Chinese language system (lexical system, grammatical system, etc.).

2.4 The complexity of the part-of-speech behavior of De “的, 地, 得” is not only a present-day issue, but also a historical one. But the complexity of this issue exceeds the scope of this article; here we only intend to discuss it briefly:

De “的, 地, 得” first appeared around the 9th century CE; during the Tang and Song periods it was generally written as “底,” and there are also instances of “地.” “底” was mainly used in attributive-middle structures, and could also be used in adverbial-middle structures; “地,” by contrast, seems at first to have been merely a suffix in words like “蓦地” “忽地” “特地” “暗地,” and later grammaticalized into a grammatical marker for adverbial-middle structures, though its usage was not very widespread, and was even less common than “底.” In the Yuan and Ming periods, “底” was replaced by “的,” and its use became increasingly widespread; Water Margin basically uses only “的,” with “地” used in a few places. By the Qing dynasty, “的” reigned supreme; Dream of the Red Chamber and The Scholars use only “的.” In the Republican period, especially after the promotion of the Vernacular Movement, influenced by Europeanized grammar—particularly English grammar—many language workers advocated the differentiation of De “的, 地, 得” in writing, such as using “底” to mark possessive relations, “的” to mark other attributive-middle relations, and “地” to mark adverbial-middle relations, and so on; but basically, these De “的, 地, 得” were still mixed at will. After the founding of the PRC, with the promulgation of the 1956 Tentative System of Chinese Teaching Grammar, the distinction among “的, 地, 得” began to be gradually and strictly implemented in teaching and publishing; their division of labor became clear, serving in turn as grammatical markers for attributives, adverbials, and complements. Even so, the phenomenon of mixing “的, 地, 得” still occurs from time to time and has never ceased to this day. And in view of the facts that De “的, 地, 得” are identical in pronunciation, complementary in distribution, historically related, and not confused in speech but often confused in writing, many people have begun to advocate unifying the written De “的, 地, 得” as “的,” or unifying “的, 地” as “的” while retaining the distinction between “的” and “得.” The latter view holds that in sentences like “这两个花瓶小得有意思” and “这两个花瓶小的有意思(大的不怎么样),” retaining the written difference between “的, 得” is more conducive to understanding and expression. However, these proposals have not been adopted to this day.

In the commonly used Modern Chinese grammatical system, “的, 地, 得” are generally considered structural particles, and these three words constitute a subcategory of particles: structural particles. The historical review of the evolution of De “的, 地, 得” above also basically describes it by ideally simplifying it as structural particles, and this indeed is the most typical and principal grammatical function of De “的, 地, 得,” namely, linking a modifier and a head to form a “modifier + De ‘的, 地, 得’ + head” phrase (the order of modifier and head can be swapped). This suggests that when analyzing the structure of De “的, 地, 得”-character phrases, we must pay attention to its relationship with “modifier + De ‘的, 地, 得’ + head” phrases.

3. De “的, 地, 得”-character Phrases

3.1 The De “的, 地, 得”-character phrases referred to in this article are phrases that contain “的, 地, or 得.” Here, “phrase” can sometimes also be a grammatical structure that adds sentence intonation, has a predicative function, and is of length greater than or equal to a phrase—i.e., a sentence. However, sentences in which “的” is used at the end of the sentence and has a distinguishing, sentence-forming meaning, expressing affirmation, judgment, emphasis, and other modal nuances, are not included. The “的” here is actually used as a modal particle and can be noted as “的气.” We believe that “的气” may have some connection with De “的, 地, 得,” but it does not belong to De “的, 地, 得.” The best example is that “的气” has already become highly differentiated and must appear within a sentence, whereas De “的, 地, 得” generally can exist at the phrase level as standby units for sentences.

3.2 According to written form, De “的, 地, 得”-character phrases can be divided into “的”-character phrases, “地”-character phrases, and “得”-character phrases. According to the position of De “的, 地, 得” within De “的, 地, 得”-character phrases, they can be divided into De “的, 地, 得” middle phrases and De “的, 地, 得” final phrases. The relationship between the two is that all “地”-character phrases and “得”-character phrases are De “的, 地, 得” middle phrases, while “的”-character phrases can be either De “的, 地, 得” middle phrases (“的” middle phrases) or De “的, 地, 得” final phrases (“的” final phrases). The so-called “modifier + De ‘的, 地, 得’ + head” phrases in 2.4 include all “地”-character phrases and “得”-character phrases, but do not include all “的” middle phrases. From the perspective of mathematical sets, “modifier + De ‘的, 地, 得’ + head” phrases are included in De “的, 地, 得” middle phrases. It follows that the internal composition, relations, and grammatical meanings of De “的, 地, 得”-character phrases are concentrated in “的”-character phrases.

Below, relevant discussion is carried out respectively from the perspectives of De “的, 地, 得” middle phrases and De “的, 地, 得” final phrases.

3.3.1 “Modifier + De ‘的, 地, 得’ + head” phrases are the ideal form of De “的, 地, 得” middle phrases. At this time, the three words “的, 地, 得” are respectively markers for attributives, adverbials, and complements in Modern Chinese. Many grammatical works have already described in detail the characteristics of these three types of phrases from the perspectives of the word-class nature/combination type (phrase type) or functional type of the modifier and the head; we will not repeat them here. The results of such descriptions accord with our conclusions above, namely that “的” has broader combinatory ability than “地, 得,” manifested as: ① In “的”-character attributive-middle phrases, when the head is a noun, the modifier can be various word classes other than conjunctions, particles, interjections, and distinguishing words, as well as various types of phrases or sentence forms (e.g., “一碰就响的桌子” “怎么处理目前局势的问题” “小王去北京的事情”). In addition, “的” can also be inserted into subject-predicate phrases, giving the entire phrase nominality and forming an attributive-middle structure, such as “这本书的出版” “春天的到来,” and so on. ② In “地”-character adverbial-middle adverbials, the head must be predicative (verb/adjective), and the modifier before it is generally an adjective, verb, some nouns, certain reduplicated forms, and certain idioms (e.g., “自言自语地说”). ③ In “得”-character predicate-complement phrases, the predicative head comes first, and the modifier after it is generally either predicative grammatical components (adjectives, verbs; subject-predicate phrases, adverbial-middle phrases), or sentences expressing the result of an action or modality. In short, the combinatory situations of “的, 地, 得” in “modifier + De ‘的, 地, 得’ + head” phrases are not easy to explain clearly within limited space, but as far as their combinatory ability is concerned, “的” is undoubtedly the strongest.

The above is actually an analysis of “modifier + De ‘的, 地, 得’ + head” phrases from the level of syntactic combination, and our comparison of the complexity of the part-of-speech behavior of “的, 地, 得” is also mainly derived from this. But if we look from the perspective of the deep semantic relationship between “modifier—head,” especially from the perspective of the semantic orientation of the modifier, we will find that the superficially most complex “的”-character attributive-middle structure has the simplest semantic relationship between its front and back syntactic components. The “syntax—semantics” relationship between the modifier and head before and after “的, 地, 得” is worth pondering.

From the perspective of semantic orientation, in “的”-character attributive-middle adverbials, the semantic relationship between the syntactic components before and after “的” is always that the “modifier” points to the “head,” or more precisely, there is always some kind of semantic connection between the “modifier” and the “head,” without exception. For example, judging from the syntactic components before and after “的,” “我的哥哥” has a kinship relationship (possession), “下午的会” has a “time—event” relationship (restriction), “研究的问题” has an “action—object” relationship (restriction), “暂时的困难” has an “evaluation—event” relationship (description), “走的人” has an “action—agent” relationship (description), “这本书的出版” has a “thing—event” relationship (reference), and so on. We may be wrong in our analysis of their specific semantic relationships, but the relationship does exist; a simple method is to appropriately add/delete/reorganize the “的”-character attributive-middle structures. For example, “我的哥哥” can become “哥哥是我的,” “下午的会” becomes “会在下午” (a possible answer to “什么时候开会”), “走的人” becomes “人走(了),” “这本书的出版” becomes “出版(了)这本书” or “这本书出版(了)”… Before and after such add/delete/reorganization, the semantic relationship between the syntactic components before and after “的” may change, but this method undeniably confirms that there is a direct semantic connection between them.

But the syntactic components before and after “地, 得” often do not have a direct semantic association; or rather, the semantic orientation of the modifier part in “地”-character adverbial-middle phrases and “得”-character predicate-complement phrases often has nothing to do with the head they are syntactically associated with, causing a mismatch in the “syntax—semantics” relationship. For example, in “地”-character adverbial-middle phrases:

- 他喜滋滋地炸了盘花生米。

- 他早早地炸了盘花生米。

- 他脆脆地炸了盘花生米。

In examples (1) to (3), “喜滋滋,” “早早,” and “脆脆” semantically point respectively to the subject (the agent of the action) “他,” the predicate core (the action itself) “炸,” and the object (the patient of the action) “花生米.” And in “得”-character predicate-complement phrases:

- 这件事好得很/他事情做得得慢吞吞的。

- 衣服被洗得干干净净/书包里塞得满满的。

- 他跑得快/这事说得清楚。

In example (4), the modifiers (很, 慢慢的) semantically all point to the predicate core; in example (5), the modifiers (懂, 干干净净, 满满的) semantically all point to the subject; while in example (6), the modifier can point to either the subject or the predicate core, creating ambiguity.

Although in “的”-character attributive-middle phrases such as “两个大学的教授” there is also ambiguity, this ambiguity is caused by the semantic orientation of the modifying component (“个”) within the modifier. As for the semantic relationship between the two syntactic components before and after “的,” they are still directly related: “两个大学” always refers to “教授.” In other words, the “syntax—semantics” relationship of the “的”-character attributive-middle structure is one-to-one: the modifier in the phrase always semantically points to the head.

3.3.2 The previous subsection was a strict discussion of the ideal form of De “的, 地, 得” middle phrases, but in actual usage, there is also a non-typical “的” middle phrase that is structurally similar to the “的”-character attributive-middle phrase, such as “他的老师” in “他的老师当得好.” If we compare this sentence with “他的老师” in “他的老师教得好,” we will find: the “的” middle phrase in the former cannot stand alone as a sentence (or the meaning changes drastically); the “他” and “老师” before and after “的” actually refer to the same person, i.e., they are in an appositive relationship; whereas the “的” middle phrase in the latter is a “的”-character attributive-middle phrase, which can be used independently as a sentence, and “他” and “老师” have a possessive semantic relationship. This means that these two sentences, which superficially have the same structural hierarchy, may be two different sentence patterns.

This article holds that for “的” middle phrases of the type in “他的老师当得好,” we should analyze more from the pragmatic level or functional level, which is precisely what the academic community has relatively neglected over the past half century. This is because, as pointed out above, De “的, 地, 得” or “的” is the number one high-frequency word in Modern Chinese. Such extremely high-frequency usage provides strong momentum for the functionalization (bleaching) of the word’s part-of-speech behavior, and also causes internal differentiation in the word’s part-of-speech behavior. This differentiation may be complex and uneven, as in the unequal complexity of “的, 地, 得.” People have become aware of the complexity and unevenness of this differentiation, and use corresponding written-form means or grammatical analysis theories to distinguish it; but due to incomplete understanding or the fact of heterogeneous differentiation itself, people’s distinctions cannot be complete, and thus the standardization brought about by such distinctions cannot be thorough. A reasonable result is that the complexity and unevenness of the word’s part-of-speech differentiation will exist dynamically for a long time, with the duration constrained by the entire language system and directly related to the word’s usage frequency. Applying this theory to De “的, 地, 得” or “的,” our conjecture is: due to extremely high frequency of use, the three written variants of De “的, 地, 得” will exist for a long time, and people’s mixing of them—especially the phenomenon of using “的” to replace “地, 得”—will also exist for a long time; the two situations will remain in dynamic equilibrium. Or in other words, the simple part-of-speech behavior of “地, 得” and the complex part-of-speech behavior of “的” will both be maintained for a long time. On this basis we further infer: due to extremely high frequency of use, similar occurrence environments, and identical phonological forms, the part-of-speech behavior of “的” in non-typical “的” middle phrases, in addition to being directly influenced by the “的” of “的”-character attributive-middle phrases, is also influenced by the “地, 得” usages in De “地, 得”-character phrases. By hypothesizing “的, 地, 得” as a single De “的, 地, 得,” we imply this layer of meaning. This article attempts a simple proof as follows:

First, “他的老师当得好” is clearly a sentence pattern with very strong pragmatic or colloquial coloration. Similar sentences include “他的篮球打得好,” “他的三千米拿了金牌,” “去,别扫大家的兴,” “你走你的阳光道,我走我的独木桥,” “他看了两天的书,” “他看了两场的电影,” and so on. Compared with sentence patterns like “他的老师当得好,” the former are extremely rare in written language; when they do appear, it is generally in passages that reflect colloquial color, such as character dialogue in novels, whereas the latter can be seen everywhere. In fact, since this is a pragmatic phenomenon, as long as the language differentiation is produced by pragmatics, there will always be transitional forms between the “pragmatic—written” poles, such as “他的头发理得不错,” “她的鞋做得好看,” “他的马骑得很累,” “她的毛衣织得好,” which can be either of the “他的老师当得好” type or of the “他的老师教得好” type. Lü Shuxiang believed that “他的针扎得不疼” can have three layers of meaning: his needle is used for acupuncture and it doesn’t hurt; he gives others acupuncture and they don’t hurt; others give him acupuncture and he doesn’t hurt. The existence of transitional forms shows the stability of the degree of differentiation of “他的老师当得好”-type sentences; they can be viewed as a sentence pattern, except that due to their pragmatic nature, this pattern has not been widely used in writing.

Second, although the level of spoken use and the level of written use sometimes have a certain insurmountable boundary, there can still be profound analogical relationships between the two, or “form-borrowing phenomena.” For example, regardless of what analytical method is adopted, no one would deny that the “的” middle phrase in “他的老师当得好”-type sentence patterns originates from a transplantation or borrowing of “的”-character attributive-middle phrases. This transplantation or borrowing is not only a holistic, structural transplantation and borrowing (e.g., the whole phrase can and can only serve as subject and object); even the internal semantic relationship before and after “的” is not without similarity. For example, as far as we currently see, in the vast majority of “他的老师当得好”-type sentence patterns, the “modifier” part and the “head” part of the subject and object are still directly related. Taking the examples in the previous paragraph: in “他的老师,” “老师” is “他”’s identity; in “他的三千米,” “他” is the agent of the “三千米 (run)” action; in “扫大家的兴,” the “兴” (interest) is owned by “大家”; “阳光道” and “独木桥,” as two locations, emphasize that it is “你” and “我” who “走” them rather than others; “两场” indicates the “quantity” of times the “电影” is shown; and so on. Hu Jianhua once used the example “你去捧你的梁朝伟的周瑜去吧,我还是喜欢我的林青霞的东方不败” to point out the limitations of Huang Zhengde and others’ formal-syntactic analysis of “他的老师当得好.” In fact, in this sentence, “东方不败” is the role played by “林青霞” in the film, and this role is liked by “我,” so that in the speaker’s mind there is some kind of subjective possessive relationship among the three; as for the relationship among “你,” “梁朝伟,” and “周瑜,” it is the same, a kind of psychological analogy made by the speaker from the listener’s standpoint. Thus, the analogical relationship between the “的” middle phrase of “他的老师当得好”-type sentence patterns and “的”-character attributive-middle adverbials can be established.

Finally, pragmatic phenomena are extremely complex, and their ins and outs often cannot be clearly disentangled by people. The view of this article is: within the entire language system, just as there are differentiated variants within a word’s part-of-speech behavior, there are always various forms of analogy phenomena, but the analogical process is intricate and difficult to depict. For example, within the entire language system, many people believe that “他的老师当得好”-type sentence patterns are a blending of other sentence patterns and “的”-character attributive-middle adverbial structures, such as:

- 他的老师当得好——他老师当得好——他当老师当的好。

- 他的篮球打得好——他篮球打得好——他打篮球打得好。

- 他的三千米拿了金牌——他三千米拿了金牌——他跑三千米拿了金牌/*他拿三千米拿了金牌

- 去,别扫大家的兴——去,别扫大家兴——大家的兴。

- 别生我的气——别生我气——*我的气。

- 你走你的阳光道,我走我的独木桥——你走你阳光道,我走我独木桥——你的阳光道/我的独木桥。

- 你静你的坐,他示他的威——你静你的坐,他示他的威——你的坐/*他的威。

- 他看了两天的书——他看了两天书——*两天的书。

- 他看了两场的电影——他看了两场电影——两场的电影。

This article has no intention of analyzing the above examples in detail, nor is it easy to analyze them clearly within limited space, but it can be seen from this: even if they are all “的”-character phrases that are not attributive-middle structures, their internal usage situations are extremely complex and cannot be generalized.

3.3.3 The “的” in the “的” middle phrase of the “你什么时候来的北京”-type sentence pattern is generally considered a tense-aspect particle, usually used between the predicate and the object, indicating affirmation of a completed event, which is quite different from the structural particles “的, 地, 得” that only express structural meaning. This article holds that the “的” here is not a tense-aspect particle at all, but rather a modal particle, namely “的气.” As in the following sentence patterns:

- 你(是)什么时候来的北京?——你(是)什么时候来北京的?

- 我(是)在城里读的高中。——我(是)在城里读高中的。

- 这是我在城里读的高中。——*这是我在读城里高中的。

- 我本来准备写信的,但后来不小心忘记了。——*我本来准备写的信,但后来不小心忘记了。

In examples (16) and (17), the so-called tense-aspect particle can both be placed at the end of the sentence to express an affirmative tone. We have added an omitted or implicit “(是)” between the subject and the adverbial-middle phrase in the two sentences to show that in sentence patterns where this kind of “tense-aspect particle” appears, the in-sentence focus or new information position is on the adverbial (usually a time or place adverbial), rather than on the object. Therefore, when the focus of example (17) shifts from the adverbial to the object, “的” becomes (in fact, it is not “changed” out, but collocated out) a structural particle rather than a modal particle; compare example (18). In addition, if the focus of the sentence is not on a time or place adverbial, then sentence-final “的气” cannot be moved to between the preceding predicate-object phrase, as in example (19). In short, the environment in which the “的” in “你什么时候来的北京”-type sentence patterns occurs (a predicative “的” middle phrase) itself contains the tense feature of “event completed,” so “的” here does not convey any tense information. If “的” is omitted, the focus of the whole sentence becomes unclear; at this time, whether the whole event occurred should be judged according to the specific context; compare: “我九点来北京,十点入住宾馆……一直在那住了几天才离开/决定在那住上几天再离开”. Therefore, “的” cannot be a tense-aspect particle.

Although the above “的” is not at all the same word as the “的” in the two preceding subsections, structurally speaking, the “的气” middle phrase is obviously influenced by ordinary “的” phrases, and this influence is also likely to have come from analogy. For example, in the counterfactual sentences of the above patterns, although “的” can be omitted, it cannot be moved to the end of the sentence. For example:

- 如果我九点来(的)北京,现在人就已经在宾馆里面了。——*如果我九点来北京的,现在人就已经在宾馆里面了。

- 如果我在城里读(的)高中,现在可能就能去更好的大学读书。——如果我在城里读高中的,现在可能就能去更好的大学读书。

It can thus be seen that analogy is an extremely complex linguistic phenomenon; it can even be only structural analogy while being completely unrelated functionally. This conclusion lends credibility to our analysis above.

3.4.1 De “的, 地, 得”-character phrases also have another important sentence pattern, namely De “的, 地, 得” final phrases, or more precisely, “的” final phrases. Therefore, this section will collectively refer to them as “的” final phrases (excluding “的气” final phrases). In the commonly used Modern Chinese grammatical system, this kind of sentence pattern is generally directly called a “的”-character phrase, but in fact the “的”-character phrases here are included within the “的” final phrases of this article. This is because, similar to “的” middle phrases, “的” final phrases also have a class of non-typical sentence patterns, which cannot be covered by the ideal form of “的”-character phrases. That is to say, in a portion of “的” final phrases, the head actually does not exist; in the terms of formal syntax, it can be regarded as an empty item (empty item). But in terms of the functional type of the whole phrase, both are nominal, and are typically used as subjects and objects. Therefore, in 2.1 we pointed out that, in terms of the ideal relationship of De “的, 地, 得”-character phrases, De “的”-character phrases are nominal phrases.

3.4.2 In terms of the ideal form, “的” final phrases can roughly be regarded as being formed by “modifier + 的 + head” with the head omitted, or in other words, derived by omitting the head from “的”-character attributive-middle phrases. Of course, the reverse of this statement does not hold: the head of some “的”-character attributive-middle phrases generally cannot be omitted.

In terms of phrase composition, the modifier of “的” final phrases can be nominal components or predicative components. A brief description follows:

① Nominal component + 的[+ potential head]. Generally speaking, when the potential head refers broadly to people or specific items, the phrase can simultaneously be a “的” final phrase and a “的”-character attributive-middle adverbial, as in examples (22) and (23); when it refers to a person’s title or an abstract thing, the phrase can only be a “的”-character attributive-middle phrase, as in example (24).

- 你们班的(同学)到齐了没有?

- 这是他的(行李)。

- 我们的(意见)是明天去,他的(意见)是今天就走。

② Predicative component + 的[+ potential head], which can further be divided into two subtypes:

-

Adjectival component + 的[+ potential head]. Generally speaking, if the attributive is restrictive or classificatory, the phrase can simultaneously be a “的” final phrase and a “的”-character attributive-middle adverbial, but in spoken language generally only the “的” final phrase is used, as in examples (25) and (26); if it is descriptive or has strong emotional coloring, the phrase can only be a “的”-character attributive-middle phrase, as in example (27):

- 他有两个小孩,大的(小孩)十岁,小的(小孩)七岁。

- 找到目击证人这是最重要的(事情)。

-

美丽的(花朵)/光辉的(形象)/宏伟的(蓝图)/热烈的(场面)

-

Verbal component + 的[+ potential head]. Generally speaking, if the verbal component and the potential head have an implicit subject-predicate or predicate-object relationship, the phrase can simultaneously be a “的” final phrase and a “的”-character attributive-middle adverbial; otherwise it can only be a “的”-character attributive-middle adverbial.

- 看比赛的(人)很多。

- 他唱的(歌)是流行歌曲。

- 他游泳的(*姿势)不正确。

- 伴奏的(声音)太大而唱的(声音)太小。

From this it can be seen: the ideal form of “的” final phrases is obtained from “的”-character attributive-middle phrases by omitting the head through reliance on a certain context; it is also a phenomenon in which a usage at the pragmatic level stably permeates into written language.

3.4.3 The existence of non-typical “的” final phrases again confirms our argument about language analogy. If typical “的” final phrases are obtained under the作用 of context by omitting the head in “的”-character attributive-middle structures, then non-typical “的” final phrases are obtained by omitting non-typical “的” middle phrases through analogical action among different differentiated variants within the part-of-speech behavior of “的.” This is manifested in that a considerable number of non-typical “的” middle phrases, under certain contexts, can omit the “head” after “的” and become “的” final phrases, and this omission can occur in classes, such as:

- 他的老师当得好。——他的当得好(回答“哪个老师当得好?”)。

- 他的篮球打得好。——他的打得好(回答“谁的篮球打得好?”)。

- 你走你的阳光道,我走我的独木桥。——你走你的,我走我的(因为此句是熟语,省略点可能在表达色彩上会有不同)。

- 你念你的书,我睡我的觉。—— 你念你的,我睡我的。

Of course, in many non-typical “的” middle phrases the “head” cannot be omitted, or the meaning changes drastically after omission, such as:

- 他唱他的青衣——*他唱他的(意思大变)

- 你静你的坐,我示我的威——*你静你的,我示我的

- 扫大家的兴/告他的状/生你的气/介他的意——*扫大家的/告他的/生你的/介他的

- 他看了两场的电影——*他看了两场的

- 你去捧你的梁朝伟的周瑜去吧,我还是喜欢我的林青霞的东方不败。——?你去捧你的,我还是喜欢我的。

From this it can be seen how complex the process is of obtaining non-typical “的” final phrases by omitting the “head” from non-typical “的” middle phrases.

In addition, some non-typical “的” final phrases cannot be obtained by omitting the “head” from non-typical “的” middle phrases. For example:

- 他哭他的,我笑我的。

- 去你的!

- 这个会,你的主席,他的秘书。

- 这一场,梁朝伟的周瑜,林青霞的东方不败。

Of course, we can still try to explain: examples (41) and (42) are still obtained by analogy with sentence patterns like “你念你的书,” except that because “哭,” “笑,” and “去” are non-governing intransitive verbs, no component can be supplied after “的”; examples (43) and (44) are due to a very special context, in which the “head” after “的” is hidden according to usage habits and cognitive patterns. If one wants to supply the hidden information, such sentences can be transformed into “的”-character attributive-middle structures or the ideal form of “的” final phrases by adding the head, such as:

- ’这个会,你的(角色是)主席,他的(角色是)秘书。

- ‘这一场,梁朝伟(演)的周瑜,林青霞(演)的东方不败。

3.4.4 In summary, language use is an extremely complex process, and the extremely high frequency of “的” strengthens the complexity of its part-of-speech behavior through repeated use. But undoubtedly, the formation of “的” final phrases is closely related to the extremely high frequency of “的” and the analogical作用 of language.

Comments