Some Thoughts on "De

Disclaimer: This post was originally written in Chinese and translated into English by GPT-5.2.

- A New Discussion of the Tense Particle “de”

The character “的” is a function word of extremely important status in the lexical system of Modern Chinese. The prevailing Modern Chinese grammatical system holds that there are three “de” function words: structural “de,” modal “de,” and tense “de.” However, based on our investigation, we believe that the so-called tense “de” in fact does not exist; its real part-of-speech nature should be the modal “de.”

It is generally believed that the “de” in the following two examples is a tense particle:

- When did you come to Beijing?

- I attended high school in the city.

Relevant analyses hold that, in the two sentences above, “de” conveys that the event has already occurred, and therefore is a tense particle, typically used between the predicate and the object. But in the above contexts, the two sentences can be rewritten as:

- When was it that you came to Beijing? — When was it that you came to Beijing?

- It was in the city that I attended high school. — It was in the city that I attended high school.

In the two sentences above, we inserted an omitted or implicit “(是)” between the subject and the adverbial phrase, in order to show that, in this type of sentence pattern where the “tense particle” appears, the position of new information or focus in the sentence is on the adverbial (usually an adverbial expressing time and place), rather than on the verb–object structure that expresses the event afterward. That is, the events in the two sentences above are all old information within the sentence; therefore these events have all occurred (otherwise they would not become old information). Thus, the “de” in the sentence can be moved to the end of the sentence without changing the semantics of the whole sentence. And when “de” is moved to the end of the sentence, it is purely a modal particle, expressing a confirming tone, while also marking old information (with new information in front). We believe that, in the process before and after this movement, “de” has not undergone a change in part of speech, so it is in both cases the same modal particle “de,” and there is no such thing as a so-called tense particle “de.”

We can also delete the “de” in both sentences, obtaining the following two new sentences:

- When are you coming to Beijing?

- I attended high school in the city.

Although example (5) can generally be rewritten as “When will you come to Beijing,” asking about an event that has not yet occurred, here the reason the event is not yet occurred is conveyed by the structure of the entire sentence: first, the whole sentence is an interrogative, and the focus of the question lies in the time when the event occurs; second, the predicate core of the whole sentence is modified only by the interrogative focus expressing time and is not delimited by other components; sentences with the structure “Agent + when + event?” are generally used only to ask about events that have not yet occurred, such as “When will you do your homework?” “When will you go to class?” But after the modal particle “de” expressing an affirmative/confirming tone, the predicate core is constrained, showing a strong old-information coloration; at this time people generally default that the event has already occurred, rather than not yet occurred, and the whole sentence thus becomes a question about specific details of an event that has already happened. There may be profound cognitive reasons behind this, which this article does not intend to discuss. But we can still make a simple comparison: in sentences of the type “Where did you attend high school,” although they are also interrogatives, the event in the sentence may have occurred, may be occurring, or may not yet have occurred, e.g.: “Where did you attend high school before?” “Where are you attending high school now?” “Where do you plan to attend high school?” And among these three questions, the first two can both be answered with the sentence in example (6), from which we can see that whether the event in example (6) has occurred must be judged based on a certain context. Even for a declarative sentence like example (5), such as “I’m coming to Beijing at nine o’clock,” whether this event has occurred also has to be judged based on a certain context; compare: “I’m coming to Beijing at nine o’clock; I’m at the hotel now,” and “I’m coming to Beijing at nine o’clock; I’ll check into a hotel at ten, and then plan to stay there for a few days.” It can be seen that, it seems that as long as it is not a sentence with the “Agent + when + event?” structure, the kind of sentence we usually think is marked with “de” to indicate that the event has already occurred and thus contains a tense particle, after removing “de” does not necessarily lose the semantic feature of [+event has occurred]. Therefore, the “de” in this type of construction does not have the grammatical function of distinguishing “whether the event has occurred.”

In addition, there are two interesting sentences here worth noting:

- *I came to Beijing at nine o’clock tomorrow. — *It was at nine o’clock tomorrow that I came to Beijing. — *It was at nine o’clock tomorrow that I came to Beijing. — *I’m coming to Beijing at nine o’clock tomorrow.

- *I attended high school in the city right now. — *It is right now in the city that I attended high school. — *I am attending high school in the city right now. — *I am attending high school in the city right now.

Because sentences (7) and (8) contain the two words “tomorrow” and “now,” which indicate non-past tense, the whole sentence cannot insert “de” at the original position of the “tense particle.” Why is this? We believe this is not because the “non-past tense” indicated by the time adverbial conflicts semantically with the “event has occurred” supposedly indicated by the tense particle “de,” making them unable to co-occur, because in fact these two sentences also cannot be rewritten into the three variants on the right side of the original formula. From this we can see that they cannot co-occur with the modal particle “de” that expresses confirmation and at the same time marks old information. Just as the adverbials in sentences where the so-called “tense particle ‘de’” occurs often express time and place, it can be seen that the occurrence environment of the modal particle “de” in this type of construction has conditional constraints. This constraint is that the environment it occurs in must be [+event + old information], or [+already occurred event].

In sum, in constructions such as “When did you come to Beijing” and “I attended high school in the city,” the environment in which “de” occurs (the predicative “de”-middle phrase) itself already contains the tense feature “the event has occurred,” so “de” here does not convey any tense information. The reason “de” makes people feel that it indicates that the event has already occurred is because the “de” here is an ellipsis or implicit structure of “是……的”: “是,” as a focus marker, is associated with the time or place adverbial, indicating that the focus or new information in the sentence lies on the time adverbial and place adverbial; and “de,” as a modal particle, is used here to express confirmation, and also has the function of marking old information. Precisely because the environment where “de” occurs here is an old-information environment and refers to a specific event, most people mistakenly confuse the modal particle “de” with a tense particle “de.” According to the analysis in this article, this is actually inaccurate.

(P.S.: In fact, the cognitive rationale behind it is very simple: any event has spatiotemporality; when we place emphasis on the specific time or specific space in which an event occurs, we have already presupposed this event as a past event, i.e., already occurred.)

- Analogical Extension of the Possibility of Non-typical “de” Phrases

The structure of inserting the modal particle “de” into the middle of a verb–object phrase mentioned above drew our attention. Obviously, considering only formal characteristics, this type of structure and the modifier–head phrase in which the structural particle “de” occurs can both be described as: X + de + Y. Or, in other words, disregarding differences in part of speech, these two structures can both be collectively called “de”-middle phrases. In addition, in both structures, the syntactic constituent Y after “de” can often be omitted in certain contexts, e.g. for the modal particle “de”: When did you come (to Beijing)? I attended (high school) in the city. For the structural particle “de”: my (things). things to eat (things). Based on this, we hypothesize that the reason why “de” in constructions like “When did you come to Beijing” and “I attended high school in the city” can be inserted into the middle of a verb–object phrase is that the modal particle “de” analogically imitates the structural characteristics of the structural particle “de”’s “de”-middle phrase, and thus is moved from the sentence end to the sentence middle.

We say this mainly for two reasons: first, both types of structures can be described as “X + de + Y,” and among them, the “de” modifier–head phrase is undoubtedly the typical representative of this structure; this is the primary “borrowing of form” source for the formation of the “X + de + Y” structure. Second, if we adopt the analogy account, then not only can the motivations for the formation of many non-typical “de” modifier–head phrases be explained accordingly, but many non-typical “de” phrases can also be explained. This shows that the analogy account has strong explanatory power. Below are concrete examples of non-typical “de” modifier–head phrases and non-typical “de” phrases respectively:

A. Non-typical “de” modifier–head phrases:

- He does well as a teacher. — *his teacher (meaning changes greatly).

- He plays basketball well. — *his basketball (meaning changes greatly).

- His 3000 meters won the gold medal. — *his 3000 meters.

- Don’t spoil everyone’s mood. — *everyone’s mood.

- You take your sunny road, I’ll take my single-plank bridge. — your sunny road/my single-plank bridge.

- You go and adore your Tony Leung’s Zhou Yu; I still like my Brigitte Lin’s Invincible Asia. — *your Tony Leung’s Zhou Yu, my Brigitte Lin’s Invincible Asia.

B. Non-typical “de” phrases:

- He does well as a teacher. — He does well. (answering “Which teacher does well?”)

- He plays basketball well. — He does well. (answering “Whose basketball is played well?”)

- His 3000 meters won the gold medal. — He won the gold medal. (answering “Whose 3000 meters won the gold medal?”)

- You read your book, I’ll sleep my sleep. — You read yours, I’ll sleep mine. — *my sleep.

- To hell with you!

- In this meeting, yours is the chair, his is the secretary.

Non-typical “de” modifier–head phrases and non-typical “de” phrases are undoubtedly obtained via form-borrowing analogy from typical “de” modifier–head phrases and typical “de” phrases; but whether non-typical “de” modifier–head phrases or non-typical “de” phrases, their common characteristics are that they are strongly colloquial and pragmatic, usually becoming acceptable only under certain contexts, and are rarely used in written language. This is consistent with modal-particle “de” middle phrases (e.g.: *came to Beijing. *attended high school.), and differs from the usage of typical structural-particle “de.” In addition, these three types of “de”-middle phrases cannot be spoken alone as a well-formed utterance, or, if spoken alone, their meaning changes greatly. In other words, they have a strong dependence on the sentence, which is quite different from typical “de”-middle phrases (“de” modifier–head phrases and “de” phrases) that can exist directly at the phrase level. However, all “de”-middle phrases share one common point: semantically, the syntactic components before and after “de” are basically directly related. For example: in “When did you come to Beijing,” the destination of “come” is “Beijing”; in “I attended high school in the city,” the level of schooling “read/study” is “high school”; in “He does well as a teacher,” “he” and “teacher” are the same person, and “teacher” is “his” identity; in “He plays basketball well,” “he” is the agent of “(play) basketball”; in “Don’t spoil everyone’s mood,” the “mood (interest)” belongs to everyone; in “You take your sunny road,” the “sunny road” is the location that “I” walk on. Similar analysis can be applied by analogy to “de” modifier–head phrases, and will not be repeated here.

We advocate analogy, and this can also be seen from the correspondence between non-typical “de” modifier–head phrases and non-typical “de” phrases. This correspondence is undoubtedly similar to that between “de” modifier–head phrases and “de” phrases: in certain contexts, the latter can be the product of an ellipsis phenomenon of the former, as shown in examples (15)–(18). In particular, examples (15)–(17) can only appear as answers to specific questions, showing that when the speaker uses the right-hand form to answer a question, in their mind they are using the left-hand non-typical “de” modifier–head adverbial as a general “de” modifier–head phrase. Examples (19) and (20) show that not all non-typical “de” phrases can be obtained by omitting the head component of a non-typical “de” modifier–head adverbial, which makes their existence independently motivated. If we classify by the functional types of “de”-middle phrases, we will find that non-typical “de” phrases and modal-particle “de” middle phrases are both predicative, whereas all other types of “de”-middle phrases are entirely nominal. This has two implications: first, since “de” phrases can be used as predicative phrases, this provides a parallel example for modal-particle “de” middle phrases serving as predicates. Second, since all other “de”-middle phrases are nominal (even sentences like “the publication of this book” and “the arrival of spring” are still nominal), this implies that modal “de” and structural “de” are two words with a clear distinction, not one word. The relationship between modal-particle “de” middle phrases and general “de”-middle phrases is purely a formal borrowing and transplantation.

As to why the modal particle “de” can analogically imitate the structural characteristics of structural-particle “de”’s “de”-middle phrase and thus be moved from sentence end to sentence middle, we think a possible explanation is: the identity of the two words in phonetic form and the extremely high frequency of use of “de” phrases (generally used as “de” modifier–head phrases) are the external factors that make this analogy possible. As for internal factors, perhaps modal-particle “de” middle phrases are more convenient to use and psychologically less effortful (because people are accustomed to using “de” modifier–head phrases), so ease of use may be the psychological motivation that ultimately realizes this analogy. However, all of this awaits further detailed verification.

- “de, di, de” and Part-of-Speech Classification

The internal part-of-speech differentiation within “的” reminds us of the phonetic-form-identical “的、地、得,” which can for the moment be collectively called De “的、地、得.”

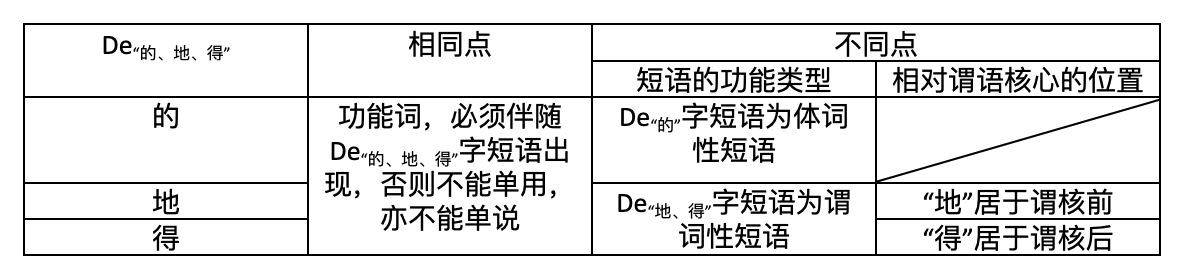

The three words “的、地、得” are all high-frequency words in the Modern Chinese lexical system, with extremely high usage frequency, and thus are all function words. These three words constitute a subclass of particles in the Modern Chinese part-of-speech classification system, namely structural particles. Ideally, the relationship among these three words is as follows:

From the table we can see:

First, “的、地、得,” without exception, are all function words, or in other words, all are empty words; they must be used within De “的、地、得” phrases, so all their grammatical functions lie in participating in the construction of De “的、地、得” phrases, and their grammatical meanings can only be manifested within De “的、地、得” phrases. From this perspective, De “的、地、得” can be regarded as a single function word as a whole.

Second, the three part-of-speech variants within De “的、地、得” can be separated out in two steps: in the first step, if the functional type of the De “的、地、得” phrase is nominal, then “的” can be separated out from De “的、地、得”; if the functional type of the De “的、地、得” phrase is predicative, and the position of De “地、得” is before the predicate core, then “地” can be separated out; otherwise, “得” is separated out.

As is well known, the written distinction among “的、地、得” is an artificial prescription, and the basis for the prescription lies precisely in the relationships shown in the table above. But in actual usage, these three words are often mixed; the typical situation is that “地、得” are written as “的,” rather than the reverse. This can also be seen from the fact that in Modern Chinese word frequency lists, the usage frequency of “的” is far higher than the sum of “地、得” (see Section 4). We believe there are three reasons:

- In actual spoken communication, the phonetic forms of “的、地、得” are identical, and this does not hinder normal communication. Therefore, even if “的、地、得” are mixed in written language, in most cases it will not cause difficulty in understanding; people can completely infer, based on everyday usage, what form the mixed De “的、地、得” should have been written as in written language, or they may not need to infer at all and instead understand directly as in oral communication.

- When people segment De “的、地、得,” which have identical phonetic forms, the criteria used before and after are not the same; that is, they do not strictly adhere to the identification principle of segmentation of grammatical units. According to the relationships in the table above, the basis for distinguishing “的” from “地、得” is their distribution in phrases of different functional types; the basis for distinguishing “地” from “得” is their distribution relative to the predicate core within De “地、得” phrases. Thus, the criteria used before and after to distinguish “的” from “地、得” are not only different, they are not even in the same level of grammatical environment; the segmentation of “的” occurs in a higher-level grammatical environment. This makes “的,” on the one hand, have broader combinatory ability than “地、得,” and on the other hand also makes the distributions of the three words complementary, providing conditions for mixing the three words without causing comprehension obstacles.

- The mixing of these three words and the dominance of “的” also have historical reasons. Here we briefly discuss the historical evolution of De “的、地、得” as follows:

The earliest appearance of De “的、地、得” is roughly around the 9th century CE; in the Tang and Song periods it was generally written as “底,” and there are also examples of “地.” “底” was mainly used in modifier–head structures, and could also be used in adverbial–head structures, while “地” at the beginning seems to have been merely a suffix at the end of words such as “蓦地” “忽地” “特地” “暗地,” and later grammaticalized into a grammatical marker of adverbial–head structure, but examples were not very widespread, perhaps even less common than “底.” In the Yuan and Ming periods, “底” was replaced by “的,” and was used more and more widely; Water Margin basically uses only “的,” with “地” used in a few places. By the Qing dynasty, “的” unified everything; Dream of the Red Chamber and The Scholars use only “的” throughout. In the Republic of China period, especially after the promotion of the Vernacular Movement, influenced by Europeanized grammar, especially English grammar, quite a few language workers advocated a written differentiation of De “的、地、得,” such as using “底” to mark possessive relations, “的” to mark other modifier–head relations, “地” to mark adverbial–head relations, and so on; but basically, these De “的、地、得” were still mixed at will. After the founding of the PRC, with the promulgation of the 1956 Provisional Draft Chinese Teaching Grammar System, the distinction among “的、地、得” began to be gradually implemented more strictly in education and publishing; their division of labor became clear, serving in turn as grammatical markers of attributives, adverbials, and complements. Even so, for the reasons above, the mixing of “的、地、得” still occurs from time to time and continues to this day.

In view of the facts that De “的、地、得” are identical in sound, complementary in distribution, historically related, and not confused in speech but often confused in writing, many people began to advocate unifying written De “的、地、得” as “的,” or unifying “的、地” as “的” while keeping the distinction between “的” and “得.” The latter view holds that in sentences like “These two vases are so small it’s interesting” and “These two vases are small and interesting (the big ones aren’t so good),” preserving the written difference between “的、得” is more conducive to understanding and expression. However, these proposals have not been adopted to this day.

The written-form distinction among “的、地、得” reflects people’s awareness of the complexity of the parts of speech of De “的、地、得.” In other words, people are aware (perhaps collectively unconsciously) that in Modern Chinese, De “的、地、得,” which share the same phonetic form, are internally complex and heterogeneous in part of speech, and can be divided into at least three types, namely De “的,” De “地,” De “得,” or “的、地、得,” and therefore consciously distinguish them in writing. But the confusion among these three words, rather than reflecting the complex usage conditions of particular De “的、地、得” variants, instead reflects the cognitive predicament people face in correspondence and conversion between spoken and written language: on the one hand, people can perceive differences among components of the language system or within a component (in sound, meaning, function, …), and accordingly have developed corresponding written conventions and theories of language analysis; but on the other hand, people’s understanding of such differences is logically not strict, not complete, and not thorough, which also manifests in the imperfections of the corresponding written conventions and language-analysis theories. For example, the part-of-speech classification of De “的、地、得” does not strictly adhere to the identification principle of segmentation of grammatical units, which is consistent with the current state of classification of the entire Modern Chinese part-of-speech system. Human cognition has this kind of logical duality; natural language also has this kind of logical duality; the two should be able to correspond to each other.

Perhaps the complexity of De “的、地、得” in part of speech is nothing more than a small facet of the complexity of the entire Modern Chinese language system (lexical system, grammatical system, …).

- Summary

Ignoring differences in written form, De “的、地、得” is very likely the single word with the most complex part-of-speech properties in the Modern Chinese lexical system. Complexity of part-of-speech properties is closely related to the frequency of use of a word. According to the statistics from the online “Modern Chinese Corpus Word Frequency List” (corpus size: 20 million characters), the frequencies of occurrence of the three words “的、地、得” in Modern Chinese are 7.7946%, 0.443%, and 0.1957% respectively, ranking 1st, 14th, and 46th in the “frequency list.” Specific statistical figures may differ slightly among sources, but “的” is always the number one most frequent word in Modern Chinese, and “地、得” also always rank somewhat later in order, remaining among the top of the high-frequency word list. In short, De “的、地、得” is undoubtedly the most frequently used word in Modern Chinese (8.43333%), far beyond what any other word can match (the total frequency of the top 11 high-frequency words excluding “的” is 8.4225%, still slightly lower than De “的、地、得”). This high frequency of use makes De “的、地、得” bear a large number of usage functions, i.e., “usages,” which to some extent explains the complexity of De “的、地、得” in part of speech. Moreover, from the fact that the part-of-speech complexity of “的” is far greater than that of “地、得,” we believe that, to a certain extent, not only can the frequency of use of a word explain the causes of its degree of part-of-speech complexity, it can also explain the reasons for the formation of word classes; for example, due to high frequency of use, “的、地、得” are all function words. Language is used, and the fundamental basis for part-of-speech classification must also be naturally occurring language in actual use; thus, the complexity of natural language also arises in use. The part-of-speech complexity of De “的、地、得” or “的,” and the unevenness of its internal differentiation, may be nothing more than a microcosm of the complex and heterogeneous Modern Chinese language system. Or perhaps people have not yet developed a corresponding perfect set of coping solutions.

The complexity of the internal part-of-speech differentiation of “的” (with identical phonetic form), together with the extremely high frequency of “的” itself, makes internal analogy possible. This analogy can be a comprehensive analogy in both structure and function, such as the analogy of non-typical “de” modifier–head phrases and non-typical “de” phrases to typical “de” modifier–head phrases and typical “de” phrases; this analogy may also be merely a structural form-borrowing analogy, such as the analogy of modal-particle “de” middle phrases to general “de”-middle phrases. This analogy account has strong explanatory power, but the cognitive mechanisms behind such analogy still await study.

This article also argues in detail for the part-of-speech essence of the so-called tense particle “de,” namely the modal particle “de” that expresses confirmation while also marking old information. We also explain that the reason the modal particle “de” here is regarded as a tense particle indicating that the event has already occurred is because the occurrence environment of the modal particle “de” in this type of construction is conditionally constrained: the constraint is that the environment must be [+event + old information], or [+already occurred, completed event]. This means that the study of “de” must be analyzed case by case, requiring detailed investigation, and cannot rely solely on language intuition.

The late linguist Mr. Zhu Dexi, “over more than forty years of working on grammar, for ‘de’ he was worn down and haggard,” and in the course of this research, pioneered the use of or proposed many important methods and concepts in Modern Chinese grammatical research, with abundant achievements. His student Yuan Yulin commented that “a tiny ‘de’ character tugs at the overall situation of Chinese grammar,” which is indeed apt. But research on “de” still has a long way to go. This article offers a modest contribution and hopes to be of some effect!

Comments