On the "Sentence-Centered" Concept in The New Chinese Grammar

Disclaimer: This post was originally written in Chinese and translated into English by GPT-5.2.

Abstract: Li Jinxi is a renowned master linguist of China. His Li-style grammar and the pioneering idea of “sentence-based” (“句本位”) once influenced several generations and possess strong vitality. Although this influence, due to the prevalence of the structuralist grammatical system in China, is no longer conspicuous in the modern Chinese grammar system, in fact, we have consciously or unconsciously inherited a considerable part of its core ideas. Newly Written Grammar of the National Language marks the establishment of Li-style grammar and is also representative of it. This paper mainly takes the “sentence-based” idea embodied in this “pioneering work of modern Chinese grammar” as an entry point, attempting to reveal its “origin and development,” and hopes that such a revelation can play a modest role in helping us better inherit the essence of traditional grammatical thought and integrate the modern Chinese grammar system.

Keywords: Li Jinxi, Newly Written Grammar of the National Language, sentence-based, etymological view, Li-style grammar

1 Introduction

Li Jinxi (1890–1978) is a renowned master linguist of China. He produced an extremely rich body of writings throughout his life, covering every aspect of linguistics, and exerted a non-negligible influence on many areas, including linguistic research in China, the popularization of grammatical knowledge, the promotion of the national language movement, the advancement of script reform, and the training of talent in linguistic circles. Zhou Youguang honored him as a Chinese “pioneer and mentor of the modernization of language and writing,” which is by no means empty praise. Among Li Jinxi’s many influences, the most representative is none other than Newly Written Grammar of the National Language (hereinafter referred to as Newly Written).

The first edition of Newly Written appeared in 1924 and is China’s “pioneering work of modern Chinese grammar.” (Hu Mingyang, 2002) Guo Shaoyu (1980) said in “In Praise of Mr. Li Shaoxi”: “The study of grammar was established by Elder Li,” and Newly Written is precisely what “Elder Li” relied on to establish “the study of grammar”! According to Li Zeyu (2007), the publication data of Newly Written before 2007 are roughly as follows: “On the mainland, the Commercial Press printed a total of 24 editions from 1924 to 1959; in 1992, the Commercial Press included it in the Chinese Grammar Series as a new edition. In 1997, the Shanghai Bookstore selected it into the Republic of China Series. In Taiwan, the Commercial Press reprinted it twice in 1968 and 1969. In addition, a Japanese translation, Li’s Chinese Grammar, was published in Japan in 1943.” According to Li Wumo’s textual research, “Japanese scholars translated and adapted Newly Written Grammar of the National Language and related works,” with “more than thirty” important ones; “over a dozen papers published in the special supplementary issue of Chinese Language (1940) titled Issue on Chinese Grammar Studies almost all cited and consulted Newly Written Grammar of the National Language,” so it can be said that “Newly Written Grammar of the National Language gradually came to occupy a dominant position in the Japanese field of Chinese language teaching at that time.” In the summer of 1986, Ijichi Zen, vice-chairman of the China–Japan Education Roundtable, who came to Beijing to attend the “First International Symposium on Chinese Language Teaching,” personally told Li Jinxi’s daughter Li Zeyu: “Eighty percent of the participants have been nursed on Mr. Li’s ‘milk’.” In short, the tremendous influence of Newly Written is beyond doubt.

However, since reform and opening up, as structuralism gained mainstream status in grammatical circles, Li-style grammar was subjected to concentrated criticism, and amid a chorus of denunciation, “Mr. Li Jinxi and Li-school grammar as well as traditional grammar have since been completely negated, to the extent that in the 1980s and 1990s, attempts to publish a complete works or collected writings of Li Jinxi met with enormous difficulties, and to this day no publisher is willing to publish them.” (Hu Mingyang, ibid.) This does not match Li Jinxi’s academic standing. Regarding how Li-style grammar went cold in the linguistic community in the 1980s and was “effectively banned,” as well as the vicissitudes of human sentiment involved in that “lonely posthumous affair,” Xi Boxian (2010) offers vivid recollections. In its wake, “most young people today are already quite unfamiliar with it” (note: “it” refers to Newly Written. Xi Boxian, ibid.), and “the name of Professor Li Jinxi may already be somewhat unfamiliar to young students studying linguistics.” In terms of fact, these judgments are not exaggerated at all. However, in the author’s view, that Li-style grammar bore the brunt in the 1980s when structuralism replaced traditional grammar not only cannot completely negate its intrinsic value, but rather precisely shows how broad and profound its influence was—rarely matched—so much so that it had to be set up as a target to accept the harsh blame and accusations directed by structuralist grammar at traditional grammar. Of course, this may also have its limitations of the times, rooted in the academic world’s ideological remnants of the Cultural Revolution then: unless one escalated issues to a political level, one could not demonstrate one’s stance, resulting in a certain degree of overcorrection.

To be realistic, the Li-style grammatical system represented by Newly Written still has its dazzling aspects today, a point that has gradually been acknowledged by the grammatical community, especially against the current historical backdrop: structuralist grammar has performed poorly in middle-school teaching; “mother-tongue language education downplays grammar or even cancels grammar”; reflection on “returning to traditional grammar” is increasingly strong (Sun Dejin, 2010); theoretical and teaching standards in China’s linguistic circles continue to be updated; and reform of the Chinese subject in the college entrance examination has received great attention. But this recognition and reflection is still not the traditional sense of “being cautious at the end and remembering those far away”! Therefore we must continue to dig deep and continue to publicize, so that where “previous cultivation was not meticulous,” we may achieve “those who come later turn out more refined,” and beyond “continuing the lineage and recounting the ancestors,” seek “blue that is not inferior to indigo.”

Although this paper only takes the “sentence-based” idea in Newly Written as an entry point, it hopes to have the effect of using a point to bring out an area, making people aware of the scientific components of Li-style grammar and its modern significance. The insight of this significance may not be without benefit for our understanding of traditional grammar, integrating modern grammar, promoting the new and reforming the old, and bringing forth the new through innovation. And this is precisely the starting point and foothold of this paper.

2 The “sentence-based” idea in Newly Written

2.1 Introduction of methodology

When “revisiting several academic terms of Li-style grammar,” Liu Danqing pointed out: “After several decades, with the deepening of grammatical theory and Chinese grammar research, these Li-style grammar academic terms that once faded out have again shown signs of returning to grammatical works and re-illuminating their academic luster; their academic value deserves to be reassessed.” And he remarked with feeling: “Whether a term is reasonable is not merely a naming issue, but more a substantive conceptualization issue. The key lies in whether the phenomenon distilled and summarized by the term is a concept with scientificity and internal consistency and therefore worth integrating and extracting, and whether it is a concept that helps discover and distill scientific rules.”

“The reevaluation of all the values” is an important component of Nietzsche’s philosophy; it can be said to be a person’s will to power to surpass predecessors, or what Bloom calls the “anxiety of influence.” History has proven that this will and anxiety are likewise important driving forces of scientific development and progress. Precisely because this reevaluation in fact “is more a substantive conceptualization issue,” it cannot but arouse our considerable attention and require us to expend considerable effort. The several “key” standards given by Liu Danqing are equivalent to saying: in reevaluating a concept, one must first examine the scientificity of the concept’s connotation, then place the concept within the entire system to see the consistency of its extension, and finally verify, from an external-to-the-system perspective, the expected value possessed by the concept. The author believes that this “horizontal–vertical–depth” three-dimensional line of thinking is acceptable, and fully possesses the characteristics of objectivity, explicitness, rigorousness, and adequacy, meeting the basic requirements of what makes science science. Under the guidance of these prior principles, the following text, in three subsections, reevaluates Li Jinxi’s sentence-based thought. They are: the background for the proposal of the “sentence-based” idea and its original significance; the etymological view embodied in the “sentence-based” idea; and the application of the “sentence-based” idea in Newly Written. Although this division does not correspond one-to-one with Liu Danqing’s standards, it indeed adheres to their essence and strives to view the issue comprehensively.

2.2 The background for the proposal of the “sentence-based” idea and its original significance

As everyone knows, to this day China’s grammatical theories are all “imports”; there is not a single one that is indigenous—“foreign theories innovate over there, and we just follow along” (Lü Shuxiang, 1986). If one does not have a full understanding of this, one will inevitably fall into the predicament of factionalism. “If your school draws on the theories, methods, and systems of some Western school of grammar, that is ‘imitation’; if our own school draws on the theories, methods, and systems of some Western school of grammar, that is ‘innovation’ and ‘development’.” We must know: “This somewhat unpleasant reality is determined by history, not caused by our Chinese linguists.” It should be viewed objectively. In “Preface for Today” (1951), Li Jinxi clearly declared:

It is right to say that Chinese grammar ‘should not follow foreign grammar,’ but from the past to the present, all grammar books have basically been unable to follow foreign grammar completely; it is only that the way of analyzing sentences and distinguishing words is somewhat similar to English. As long as it makes sense logically and sees the规律 accurately, how do we know it is not that English sentence analysis and word distinction are somewhat similar to ours?

Anyone with a bit of common sense will reach this conclusion: completely following foreign theories while ignoring the uniqueness of Chinese grammar is in fact impossible first of all, because the Chinese imprint on Chinese grammarians is inerasable; secondly, the coupling between foreign grammar and Chinese grammar in certain respects is entirely logically possible, because universal grammar is still somewhat tenable to a certain extent. This underappreciated passage from Li Jinxi in fact well demonstrates his broad-mindedness and cultural confidence as a master linguist—neither servile nor arrogant—and can be said to be what Wang Fuzhi called “not being confused by what is the same, and not losing what is different.” The proposal of the “sentence-based” idea is precisely an embodiment of this academic spirit.

The proposal of sentence-based thought first benefited from the theoretical orientation of foreign grammars, especially the teaching orientation of school grammar. As early as 1921, Li Jinxi pointed out: “Emphasizing syntax—this is a new trend in grammar teaching worldwide,” and provided “an outline for the compilation and teaching of national language grammar.” Through teaching practice and discussions with peers, Li Jinxi formed a more complete grammatical system with sentence-based thought as its core idea, yet at the beginning of Newly Written, in “Introduction,” he did not conceal at all: “Do you all know the new trend in grammar studies lately? Simply put, it can be called ‘sentence-based’ grammar.” And he added a note: “This section adopted the views of A. Reed and others.” Lü Shuxiang also said: “Not until the early twentieth century did some grammarians, in works discussing languages with not-too-complex morphology such as English, begin to elevate syntax to an important position… Grammar books that appeared after the May Fourth Movement, starting with Newly Written Grammar of the National Language, all took syntax as the trunk. The shift of emphasis was not accidental; it was influenced by foreign grammatical works.” Sun Liangming, a disciple under Li Jinxi, also admitted: “The formation of the ‘sentence-based’ thought and system also drew on foreign grammar,” especially “Reed and Rellogg’s Higher Lessons in English.”

But even so, we cannot ignore Li Jinxi’s pioneering contribution to the prototype of “sentence pattern analysis” that has influenced to this day—sentence-based thought. The pioneering here includes realizing the “shift of emphasis” from word-based to sentence-based, and also includes Li Jinxi’s innovation and enrichment of sentence-based thought. That is to say, Li Jinxi was inspired by the scattered glimmers of foreign sentence-based thought before it had taken shape, and in China clearly led yet another new tide of sentence-based thought, whose influence has not vanished to this day. According to Wen Yunshui’s detailed textual research, the idea of sentence-basedness is not found in the more than 20 foreign grammar documents that were then “popular in China and widely used,” and the structuralist masters一路 from Saussure, Jespersen, Vendryes, Bloomfield, and so on also had no similar idea, and even consciously discarded it, such as Saussure. The “new trend” Li Jinxi spoke of most likely came from “the general trend of English school grammar in the early twentieth century” and “the linguistic view of the British anthropological school.” In any case, the sentence-based theory “has borrowing, but even more innovation.” This confirms Li Jinxi’s later statement:

I roughly remember that when I translated and pieced together this ‘Introduction’ in the early 1920s, there was no English word ‘sentence-based’; I blindly coined it. In books on general linguistics and general grammatical theory, I also did not find any discussion saying that the grammatical system of a certain language has a so-called ‘sentence-based’ orientation.

Only by understanding the meaning of this “blindly coined” can we properly understand Li Jinxi’s later words:

So-called ‘Li-school’ grammar, in terms of a ‘scientific system,’ has nothing special; everyone is researching and discussing it, and it is ‘mostly the same with minor differences’ compared with various schools. These minor differences are just an emphasis on nationalization and a bias toward creativity. In terms of a ‘disciplinary (teaching) system,’ it has things it advocates and things it opposes; it is ‘slightly the same with major differences.’ This major difference is insisting on ‘going from sentence-making to word-use, using syntax to control morphology.’

That sentence-based thought is the core of Li-style grammar is thus evident. This thought was endorsed by him for a lifetime, reflecting a scholar’s perseverance and confidence.

That sentence-based thought could not prevail abroad and ultimately took root domestically through Li Jinxi implies that sentence-based thought accords with China’s linguistic reality. When discussing the background of the emergence of sentence-based thought, we cannot ignore various factors from China and from Li Jinxi himself. These factors can be understood at two levels: drive and root.

The so-called drive refers to the stimulating factor that triggers a behavior. The outbreak of the New Culture Movement was undoubtedly one of the important drivers of the emergence of sentence-basedness. In the last paragraph of the 1924 “Original Preface” of Newly Written, Li Jinxi said: “I compiled this book not out of my longstanding wish; in truth I was spurred by the environment.” Li Jinxi’s student Yang Qinghui’s (1986) recollections can serve as corroboration:

During the May Fourth period, the New Culture Movement emerged… At that time, the dispute between classical and vernacular writing was extremely fierce. Jiayin, with Zhang Shizhao as its standard-bearer, declared: “When soliciting writings by notice, we do not accept vernacular.” National Language Weekly, founded by Mr. Li and Mr. Qian Xuantong, announced: “We welcome submissions; we do not take classical.” The two armies faced off, with clear battle lines. With the rise of the vernacular movement, demands were raised to study vernacular grammar. Under this situation, Mr. Li took the classroom as a battlefield, teaching “national language grammar,” using numerous examples to show that vernacular has rules to follow, and that its “rules” are sufficient to guide writing as “literature.” This not only played a pioneering role in the research and teaching of modern Chinese grammar, but also promoted the newly rising vernacular movement.

Second, Li Jinxi’s many years of teaching practice were also one of the important drivers of his sentence-based thought. Chinese belongs to an isolating language, lacking strict morphological changes, and mainly expressing grammatical meaning through word order and the use of function words; Li Jinxi had a profound awareness of this: “In using words and forming sentences, the national language emphasizes structure and is light on morphology.” Li Jinxi always regarded the “disciplinary (teaching) system” as more important than the “scientific system,” pursuing “Chinese grammar textbooks should meet practical needs—concise and useful.” Newly Written is first and essentially a “school grammar book,” and its writing goal is nothing more than achieving “one book with multiple levels,” so that it can satisfy “Chinese grammar courses at schools of all levels, and also be used for self-study by working cadres.” Sentence-basedness is thus the product of teaching practice that “improves at any time and varies anywhere in this grammar’s teaching method,” and after being tested in practice, it remains vibrant to this day.

Finally, the appearance of grammar books represented by Ma’s Grammar is another important driver stimulating Li Jinxi to write and expound. Ma’s Grammar, published in 1898, is one of the most important events in China’s grammatical circles—“the study of grammar began with Wentong” (Guo Shaoyu, 1980). From then on, the development of Chinese grammatical theory became “unstoppable.” It can be said that, as the first monograph on Chinese grammar in the modern sense, Ma’s Grammar, once published, left in the minds of later grammar researchers—especially early grammarians—a deep “anxiety of influence.” Jin Zhaozhi (1920) criticized: “Those who have talked about grammar in our country have always taken Ma’s Grammar as the non-discardable ancestor… Later authors, since they all take Ma’s Grammar as a model, naturally cannot avoid” the faults of mechanical copying and arbitrariness. Yang Shuda (1930) also criticized later grammars as “mostly following old patterns,” and he was “often dissatisfied” with Ma’s Grammar. Newly Written, which frequently uses “Wentong” as a reference for comparison, naturally could not avoid this convention. Li Jinxi said pointedly: “Imitating the ‘word-class-based’ grammar organization of former Grammar must be broken; merely, for the nine categories of word classes, separately collecting some patterns and examples and making nine unrelated units is the most unnatural organization of grammar books and the most unnatural process for studying grammar.” It is very clear that what Li Jinxi referred to was precisely these words in Ma’s Grammar: “The original purpose of this book is to specialize in句读, and句读 are formed by the gathering of characters. Only, when a character is within句读 it must have its place, and characters pairing with each other must follow their classes; after classifying, then proceed to discuss句读… All countries have their own Grammar; the general aim is similar, differing only in phonology and character forms.”

The shortcomings of Ma’s Grammar are obvious: it lacked a conscious awareness of comparing Chinese and Western grammar, and one-sidedly emphasized the abstract commonality of “Grammar” as universally applicable, inevitably inviting the criticism of forcing square pegs into round holes. However, some later scholars still believe that the idea of sentence-basedness is something to which Ma’s Grammar can lay claim. For example, Xu Jialu (1984) believed:

The ‘sentence-based’ doctrine in the book—“for any word, distinguish its category according to the sentence; without the sentence there is no category”—indeed comes from what Ma’s Grammar says: “characters have no definition, therefore no fixed class; to know its class one must first know what the meaning of the context is.” (p. 41 of A Brief History of Chinese Studies, edited and translated by Wang Lida, Commercial Press, 1959) This is indeed a sound argument.

And he further affirmed that “‘sentence-basedness’ arose from the soil of Chinese reality that lacks narrow-sense morphology; its core (‘distinguish categories according to sentences’) probably no one can get rid of.” That is, Xu Jialu on the one hand agreed with the statement in A Brief History of Chinese Studies translated and compiled from the Japanese scholar’s History of Chinese Linguistics Research, feeling that Li Jinxi’s sentence-basedness in substance derived from Ma’s Grammar; on the other hand, he was in effect saying that sentence-based thought is in fact a deep-seated national subconscious, in which case it is irrelevant whether there is lineage or not.

The author believes that this seemingly plausible but actually paradoxical statement in fact involves the root cause of the emergence of sentence-based thought. Without exploring the root cause, there is no way—when the background is clarified—to convincingly explain the “origin” (i.e., Section 2.3) and the “development” (i.e., Section 2.4) of sentence-basedness; likewise, we will not truly attach importance to the background and original significance of the emergence of sentence-based thought (i.e., this section). These are mutually related, and we need to conduct deeper discussion.

2.3 The etymological view embodied in the “sentence-based” idea

The proposal of sentence-based thought has its root cause, and this root cause should seek answers from internal ideas. Although ideas are often shaped by external reality and one’s own behavior, once an idea has been formed or before it has changed, a person’s every move is directly determined by it. From this perspective, sometimes it is better to say that heroes’ thoughts and their thinking about the trends of the times happen to correspond to the times, and that they merely borrowed the smooth, favorable currents of their era to become the most dazzling trendsetters in that current. Moreover, according to this view, controversial claims such as “heroes create the times” (including both unsuccessful and successful heroes) can also receive a reconciled explanation—this is merely that heroes, “not moved by fashion,” acting independently, in adverse circumstances, guided benefit by (circumstantial) momentum, created another situation in line with their own intentions; or, relying on personal judgment and insisting on their own views, when holding great power, guided harm by (power) momentum, and reversed the historical current. We do not deny that the origin of thought is rooted in external factors, hence the discussion in the previous section; but we believe that for a person with a roughly mature worldview, their words and deeds should be rooted internally, hence the discussion in this section is also quite necessary. Sentence-based thought was an academic viewpoint that Li Jinxi upheld for life; the implication therein is especially worthy of attention.

Since sentence-based thought is a new term coined by Li Jinxi, behind this term there should be a well-grounded and well-supported rationale. His rationale is:

Following the natural development of sentences as the path for learning grammar… finding out the duties and relations of each word within it, as if examining the various components of an organism…

First, based on the development of sentences, become familiar with the various positions and functions of word classes in each part within the sentence, and then continue to study the subcategories of word classes: this is an extremely natural matter. Sentences, from the simplest to the most complex forms, are like the growth of an organism… Living syntax should take the sentence as the base position.

Xiao Yaman has a unique insight. From the perspective of language philosophy, she believes that these words of Li Jinxi broke through “the two-thousand-year presupposition of linguistics,” namely the “initial etymological view” and the “sentence-combination genesis view,” and “put forward a brand-new linguistic idea: the emergence and development of syntactic structure does not come from the combination of words, but from differentiation,” that is, it “differentiates from a pre-structural matrix; while structure is produced, ‘word classes’ are also produced simultaneously.” Here the quoted “word classes” refers to “a linguistic unit whose meaning and function are far more chaotic and rich,” not yet the later minimal independently usable sound-meaning combination whose meaning is basically stable and categorized. This view is quite insightful, and in Li Jinxi’s writings there are many corresponding statements, showing that it is not accidental. For example, when discussing “paragraphs and chapters” in Chapter 19 of Newly Written, Li Jinxi compared the development of sentences to “a living tree” and the growth of an organism:

Sentences in our language should not be constructed like a machine; they should grow upward, like an organism. It is best to use a tree to symbolize a sentence with exquisite structure.

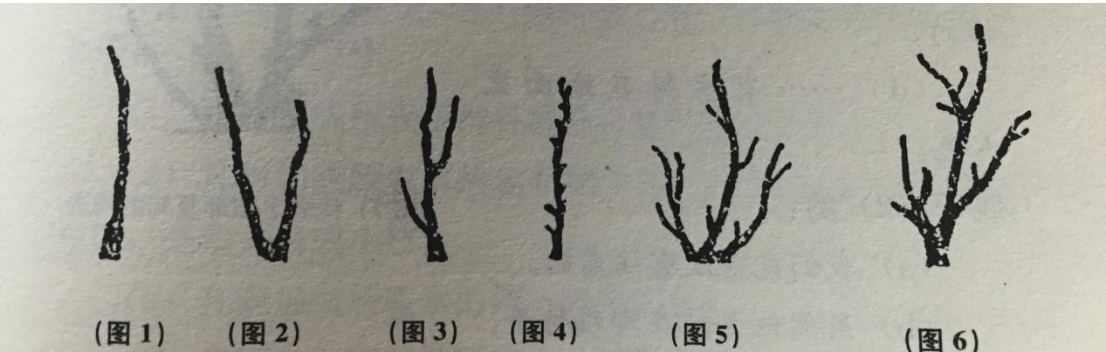

Figure 1 Single sentence. Primitive form

Figure 2 Coordinate compound sentence, primitive form

Figure 3 Main–subordinate (or inclusive) compound sentence, primitive form

Figure 4 Highly developed single sentence

Figure 5 Highly developed coordinate compound sentence

Figure 6 Highly developed main–subordinate (or inclusive) compound sentence

Xiao Yaman calls this idea of Li Jinxi the “syntactic growth-genesis view,” and believes that this “is not only an organic component of the ‘sentence-based’ view, but also the foundation of the ‘sentence-based’ systemic view,” and that “so long as one truly takes the ‘sentence’ as the starting point to view language, one will inevitably reach such a conclusion” (ibid., p. 77). The author agrees with this, and further identifies Li Jinxi’s syntactic growth-genesis view as the reason why, at the beginning of Newly Written in “Introduction,” he criticized “etymology” (Etymology) as “fragmentary” and “indifferently without anything to rely on,” because the two are fundamentally opposed. In Li Jinxi’s writings, sentences are always “organisms” and “living trees,” not “dead wood” or “dry bones.” In short, sentences are animate and dynamic. Most noteworthy is Li Jinxi’s eighth letter of correspondence with Zhang Wenhuan in his later years regarding the seven positions of content words. Setting seven positions for content words is the greatest feature of Li-style grammar and in fact also the concentrated expression of sentence-based thought. As for the reason for setting positions, he said:

The “position” has its cause—the conjecture and discovery of this cause, in the study of world “linguistics,” has a vast天地, and must start from when language first arose in primitive society.

In other words, Li Jinxi is indirectly acknowledging that his own “sentence-based” thought is in fact an embodiment of an “etymological view,” to be traced back to “when primitive society first arose”! However, “when primitive society first arose” is already extremely remote; in Li Jinxi’s words, it is “without evidence to check,” an untested chicken-and-egg problem. Since it is “without evidence to check,” then whether it is a word-etiology/etymological view or a syntactic growth-genesis view, there is no superiority or inferiority; in essence both are merely a presupposition or belief, the difference lying only in who has better explanatory power.

At this point, we have in fact returned to the question raised in the previous section, namely the relationship between Li Jinxi’s sentence-based thought and Ma’s Grammar. Exploring this relationship helps us dispel the fog of phenomena and deepen our understanding of the root cause of sentence-based thought.

The compilation of Ma’s Grammar is a typical embodiment of word-based thought—this is beyond doubt. The book is divided into ten volumes; apart from the opening and closing volumes “Volume on Correct Naming” and “Volume on Sentence Reading,” the remaining eight volumes revolve around content words and function words. And even in the opening and closing volumes, its focus of attention still cannot escape word-based thought; “to know how to断绝句读, one must first know how to gather characters to form sentences and readings,” directly shows this. This has much to do with Ma’s Grammar being deeply influenced by Western grammatical concepts. It said: “Be it Greek or Latin words… all have fixed and unchanging laws; therefore I used them to regulate our classics and the books of masters and histories—their纲 is essentially no different. Thus, based on what is the same, I assimilated those that are said to be different; this is why this compilation came to be.” We know that Western languages mainly fall within the Indo-European family; their words have rich morphology and changes of gender, number, etc. Compared with isolating languages represented by Chinese, they are inflectional languages, and such complex changes were even more evident in earlier periods. This clear difference in word classes is reflected in the thought of the Western world as deep-rooted word-basedness and word-etiology/etymological views: since words have fixed classes and classes have fixed functions, words present an absolute, separated state and correspond one-to-one with concepts, as if they were affixed to things one by one. One Hundred Years of Solitude has such a description: Macondo people afflicted with amnesia began to stick labels on objects, and stuck more and more; the semantic explanations on the labels grew increasingly complex, until when they nearly forgot all word meanings, their amnesia suddenly all recovered. This is a reverse metaphor, implying from the opposite side the relationship between things and words—sticking “labels” one by one. This is what Xiao Yaman calls the “classification naming set.” But, tracing historically and enumerating the language views of the major linguistic schools from ancient Greek philosophers through structuralism, generative grammar, and cognitive grammar, she believes that although linguistic schools since structuralism have all, at their starting points, denied the ancient Greek view that language is “a set of isolated words,” and instead endorsed Saussure’s thought that “language is a pure system of values” with internal elements organically interrelated and mutually constrained, even Saussure himself still comes from the same source but flows differently from the ancient Greek philosophers and cannot escape that hidden and hard-to-see word-etiology/etymological view. Because whether denying or affirming that language is a simple accumulation of words presupposes that words are the origin of language. Accordingly, she believes that “to this day, both Chinese and foreign [scholarship] have only language views based on words; there has not been a fundamentally ‘sentence-based’ view like Li Jinxi’s.” To this day, the mainstream of linguistics is basically so. And she adds a note: “The ‘sentence-basedness’ of Ma’s Grammar is in fact fundamentally different from Li Jinxi’s ‘sentence-basedness’.” The reason for the difference is simple: although Ma’s Grammar and Li Jinxi fully agree on the view that Chinese has “no fixed word classes,” this is merely the Chinese surface phenomenon they jointly acknowledge, or a Chinese word-class view, and has not thereby risen to an alignment of essential language views. Even if Ma’s Grammar’s “characters have no definition, therefore no fixed class” can be considered a kind of “sentence-basedness,” then compared with Li Jinxi’s sentence-basedness, it is also “each has its own right and wrong,” and must not be conflated.

Xu Jie said: in grammatical theory,所谓 “base position” refers to the core guiding principle of a grammatical system, the reliance and framework for expressing grammatical rules, the “starting point” and the “destination point.” Over a hundred years, Chinese grammar research has mainly had “‘word-based’ ‘sentence-based’ ‘phrase-based’ ‘clause-based’ ‘character-based’ ‘word–sentence dual-based’” as well as the “principle-based” he advocates. He believes: “These different base-position theories provide us with multiple windows and perspectives for observing problems,” and we should adopt “an open attitude, believing that various different ‘base-position’ doctrines are different perspectives for observing grammatical phenomena and handling grammatical problems,” that none is the most perfect, so “believe that different ‘base-position’ theories are compatible rather than opposed, complementary rather than contradictory.” The aim of this paper is an exploration of sentence-based thought, not originally a comparison of various base-position thoughts; therefore, after clarifying the background and “origin” of the proposal of sentence-basedness, we should focus on its “development,” in order to observe its explanatory power and expected value.

2.4 The application of the “sentence-based” idea in Newly Written

In the author’s view, with sentence-basedness as the core idea, the grammatical system of Newly Written includes at least the following three dimensions: From the horizontal left–right perspective, the book, for the first time, rather clearly distinguishes four levels of grammatical units: morpheme, word, phrase, sentence (character and word, phrase and sentence), and even shows the beginnings of concepts such as complex sentence and sentence group such as paragraphs and chapters. The former has already been fully absorbed and refined by modern grammar circles; as for whether the latter can be listed as the fifth major grammatical unit, it is still under debate. (Zhang Baolin 2010, Zhang Shoukang 1990) From the vertical up–down perspective, the book correspondingly establishes five types and nine classes of words, six major components and seven content positions of sentences, a diagramming method that can distinguish “literary order” and “logical order,” discusses or distinguishes ellipsis and inversion, regular forms and variant forms, simple sentences and compound sentences, clauses and subclauses, the three major types of compound sentences (inclusive compound sentences, coordinate compound sentences, main–subordinate compound sentences), and various special sentence patterns (such as ba-sentences, you-sentences, etc.), five major sentence types (declarative, deliberative, imperative, interrogative, exclamatory), and even rhetorical devices and punctuation marks. The completeness and scale of its system are not only beyond its contemporaries, but even today it remains a work with scientific organization and considerable weight! The above two points look from a two-dimensional planar space, and basically accord with Li Jinxi’s (1964) own exposition; if we add the dimension of time, we obtain the third dimension of Li-style grammar—namely the etymological view from the longitudinal front–back perspective—“the syntactic growth-genesis view.” Even in modern grammar teaching, where structuralism has replaced traditional grammar, the general grammatical system, framework, and core ideas of Newly Written, written 92 years ago, remain extremely clearly inherited in various modern grammar textbooks; its long-lasting vitality is thought-provoking.

Compared with other base positions, sentence-based theory has occupied a superior position in computer foreign-language translation and various national natural language treebanks. In the 1990s, computational linguist Huang Changning pointed out that sentence-basedness “conforms to the general trend in language analysis of combining form and meaning,” while Wu Weitian, “based on Li-style grammar, formulated a Chinese–English machine translation system of ‘distinguishing categories upon entering a sentence’ and ‘complete grammatical trees,’ and achieved initial success.” Before that, the grammar community seemed not to have recognized this; for example, Liu Danqing et al. (1984) believed that Li Jinxi’s word-class classification “is too rough,” not meeting the “precision requirements proposed by machine translation and AI research.” With further advances in computing, the superiority of sentence-basedness seems to be increasing. Huang Changning et al. (2010) pointed out: “The basic unit of a treebank is the sentence. Treebanks built for various natural languages in the world, whether phrase-structure treebanks or dependency-structure treebanks, all take the sentence as the basic unit.” This is tantamount to declaring: a grammatical system with sentence-basedness at its core has astonishing value across time and space, universally applicable to various types of languages. Li Jinxi long ago pointed out that learning sentence-based grammar “can discover the general rules of a language,” “can help in learning or translating other languages,” and “can help cultivate mental ability… to study a kind of art of thinking (how to think).” Li Jinxi’s far-sighted insight is admirable.

Although the grammatical system under sentence-basedness is “mostly the same with minor differences” from later grammatical systems, within these minor differences lies “major difference.” The sentence of sentence-basedness is living and moving, “taking the combination of symbols, i.e., structure, as the viewpoint,” and “may include dynamic pragmatic factors” (note: concrete sentences with context are dynamic sentences). By contrast, grammatical systems that take other lower-level language units as the base position either “take linguistic sign individual units as the viewpoint” or “tend toward the static syntactic level of language” (Peng Lanyu); compared with them, their one-sidedness and deficiencies are obvious. As for word-class division, those language units, being “lower in level than, shorter in length than, smaller in capacity than, simpler in structure than, and smaller in function than” the sentence, cannot observe all words in the language, and thus cannot obtain all word classes in the language (Wang Jue), far from reaching the point of fully describing the language. In the author’s view, the reason a sentence is a sentence is that a sentence “can express a complete meaning of a thought,” and is the ultimate independent sense-unit; that is, from the beginning, the grammatical system under sentence-basedness has not ignored the importance of semantics, and this is precisely the mainstream direction of international linguistic research since the 1960s. From this we can see that the grammatical system under sentence-basedness has already encompassed the three planes of semantic, pragmatic, and syntactic; its scientificity is self-evident. The long-lasting vitality of it seems not accidental either.

From a micro perspective, the most splendid, profound, and representative part of the grammatical system under sentence-basedness lies in the division of “six major components and seven content positions,” which is also the place most hotly debated in grammatical circles. The aim of this paper is an exploration of sentence-based thought, so when facing the vast grammatical system of Newly Written, it can only “outline the traces” yet keep “a small sample of feeling,” and among the “prominent general points” “take the essentials,” in the hope that “when the纲 is stretched, the目 will be lifted.”

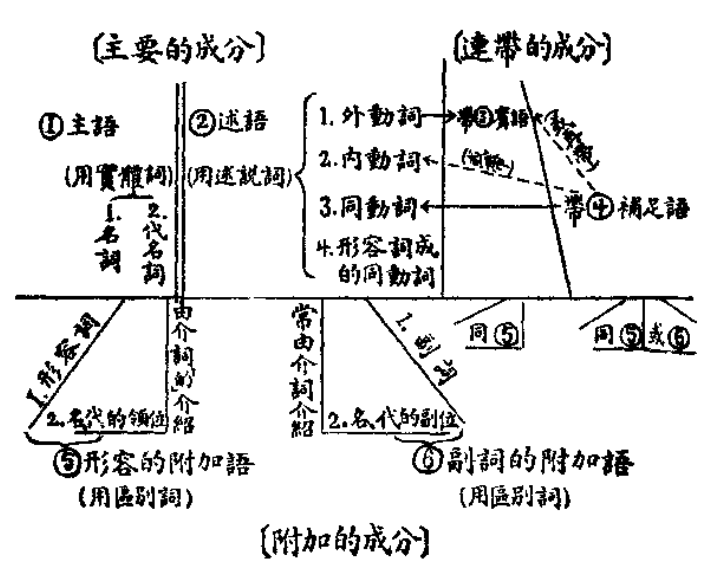

Li Jinxi (1951) pointed out: “The ‘center’ is the sentence, and the sentence’s ‘focus’ is the six major components.” These six major components also have three levels; taken together, they are: major components—subject, predicate; accompanying components—object, complement (or complement); additional components—adjectival modifier, adverbial modifier. Mapping these six components and three levels onto the general formula of syntactic diagramming yields:

Peng Lanyu (same as above) believes that this fully embodies the “system-level thinking”: “First, it can vividly reflect the structural relations of language and the hierarchical relations of primary and secondary components”; “Second, it can reflect the logical essence of language”; it “can display various parts of speech.” Li Jinxi said that his set of diagramming methods based on six major components and three levels can enable those who study grammar “to see through the literary order (note: i.e., customary language order) and discern the order of reasoning (note: i.e., logical order),” thereby “understanding what the literary order truly is,” and that “as long as the logical relations remain clear, no matter how the literary aspect shifts and changes,” one can adhere to the mean. Later Generative-Transformational Grammar has the distinction between so-called surface structure (SS, Surface structure) and deep structure (DS, Deep structure), holding that deep structure is purely logical and that, as long as one applies transformation rules (T•Rules), one can produce surface structures of diverse forms; this is in fact strikingly similar to Li Jinxi’s view. The difference is that the latter was proposed in an environment where the development of grammar was far from mature, which was not easy, and it also reflects the “universal rules underlying language.”

Peng Lanyu (same as above) believes that this fully embodies the “system-level thinking”: “First, it can vividly reflect the structural relations of language and the hierarchical relations of primary and secondary components”; “Second, it can reflect the logical essence of language”; it “can display various parts of speech.” Li Jinxi said that his set of diagramming methods based on six major components and three levels can enable those who study grammar “to see through the literary order (note: i.e., customary language order) and discern the order of reasoning (note: i.e., logical order),” thereby “understanding what the literary order truly is,” and that “as long as the logical relations remain clear, no matter how the literary aspect shifts and changes,” one can adhere to the mean. Later Generative-Transformational Grammar has the distinction between so-called surface structure (SS, Surface structure) and deep structure (DS, Deep structure), holding that deep structure is purely logical and that, as long as one applies transformation rules (T•Rules), one can produce surface structures of diverse forms; this is in fact strikingly similar to Li Jinxi’s view. The difference is that the latter was proposed in an environment where the development of grammar was far from mature, which was not easy, and it also reflects the “universal rules underlying language.”

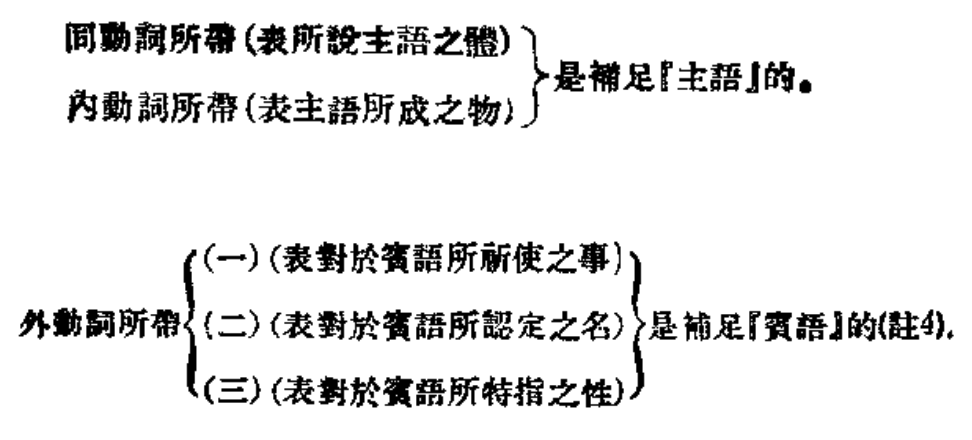

In the early 1980s, when Li’s grammar suffered a major critique from structuralism, the sentence-constituent analysis method embodied by the diagramming method was considered to have no hierarchy, or was subsumed under headword analysis; this is actually a misunderstanding. In fact, when we use the diagramming method, or diagram sentences in our minds, we of course peel away layer by layer from large to small; it is just that it may not be as clean and thorough as immediate constituent analysis, but that does not mean it has no hierarchy. Moreover, when peeling away sentence constituents, it is not only words that can serve as sentence constituents; for example, in “种花是一件很快乐的事” (“Growing flowers is a very happy thing”), “种花” (“growing flowers”) is a “loose verb” directly serving as the subject, but “种花” itself can also be regarded as a predicate-object structure, which is clearly different from headword analysis. Liao Xudong (1989) holds the same view. Another point worth mentioning is that Li Jinxi’s six major sentence components have basically been inherited by modern Chinese grammar; only in the area of the “complementing words” (补足语) is there an essential difference from the modern concept of “complement” (补语). Li Jinxi also believed that, compared with other grammatical systems, what is different about his own is “only the affiliation of ‘complements’,” and one can imagine how singular it is. Modern complements mainly refer to adjectives (a very small number of adverbs such as 很, 极 excepted) placed after verbs to explain or supplement the result, degree, direction, possibility, state, quantity, purpose, etc. of the predicate; in fact, this corresponds only to Li Jinxi’s “adverbial adjunct” (副附) or adverbial (状语), and his adverbial adjunct likewise has the above functions of modern complements (see Chapter 10 of Xin Zhu). Li’s “complementing words” (补足语), by contrast, refer to verbs (same verbs) used to explain or supplement the subject and object; the specific relations are as shown in the table below:

Liu Danqing points out: modern complements “belong only to adverbial modifying components (just postposed to the predicate core) or to components of secondary predicates.” “Li’s terminological ‘complement’ and the complement of contemporary linguistics… have the same origin, reflecting the theoretical vitality of this term. And if the prevailing Chinese grammar system cancels the concept of complementing words, it will be unable to express the phenomena and rules that the above works seek to expound.” The author believes that the discovery of complementing words is in fact a result from the sentence-based perspective; relatively speaking, his generalization is more scientific, because it reveals the influence of semantics on sentence structure, without being constrained by form and merely distinguishing syntactic components by the predicate’s relative position. “So-called Li-school grammar is, in principle, ‘using syntax to control word classes,’ while the lexical meaning of words within word classes… can in turn exert a ‘counter-effect’ to ‘resolve difficulties and disputes’ for syntactic structure,” which accords with “materialist dialectics” and is quite close to certain later views in cognitive linguistics.

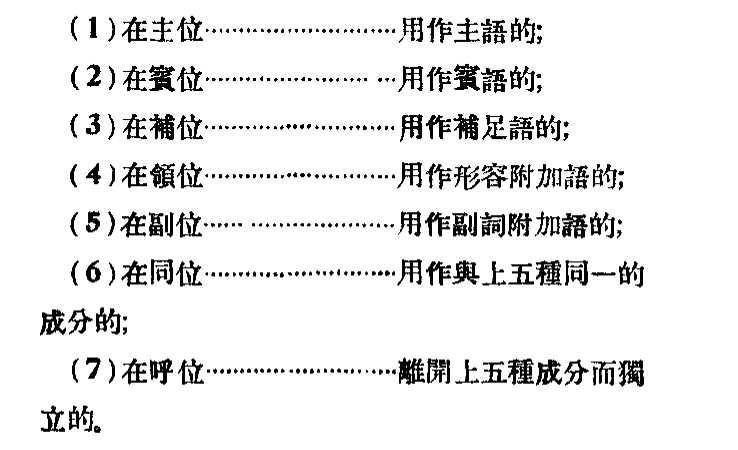

After “using the six major components to get through syntax,” Li Jinxi further “created a Chinese-specific ‘morphology’ by using seven major ‘word positions’ within ‘sentence patterns’,” which is that he “grasps the entity words (nouns, pronouns) most frequently used in Chinese vocabulary” “to control the conversion of any word class into nouns”; this is the origin of the seven positions. The specific details of the seven positions are as follows:

It is very clear that five of the seven positions are directly filled by the six major syntactic components; predicates have no position; appositive position and vocative position are two newly established items, and vocative position cannot be counted as a syntactic component. Some scholars cite He Rong’s “Why establish positions” to question the “superfluousness” of establishing positions, believing that it is entirely possible to dissolve “positions” directly under “phrases,” and modern Chinese grammar also handles it this way. However, He Rong’s words are only a general doubt of “people who read books”; in fact, he believed that entity words take the most components in sentences, accounting for 5/6, and have the highest status; “setting up an outline and establishing positions is a clever means of ‘sentence-based’ grammar,” able both to infer by analogy and to grasp the essentials. Li Jinxi’s understanding is: “Among word classes in grammar, nouns are the most numerous, pronouns (referring to ‘pronominal nouns’) are the most lively, and verbs are the busiest.” These different characteristics—their “mutual constraint laws and their interwoven ways”—are the reasons for establishing the seven positions; this also accords with Chinese realities, and is also quite similar to Fillmore’s case grammar later on, both having important significance for studying the semantic relations and syntactic configurations between nouns and the central predicate. (Hua Jianguang, Sun Jianwei) Proceeding this way, using the seven positions to control word classes solved the problem of word-class conversion in Chinese, especially the conversion of nouns, so that word classes would not undergo indiscriminate conversion without changing part of speech, and would obtain a relatively stable correspondence at the grammatical level with syntactic components; however, this is also another major reason why the seven positions were criticized. The modern Chinese grammar system holds that there is no one-to-one correspondence between word classes and syntactic components in Chinese; this is a sufficient but not necessary proposition, because which language in the world has a one-to-one correspondence between word classes and syntactic components? We know that Li Jinxi’s “positions” actually refer to word positions, or the positions of words, which are related to word order, equivalent to the English “place” or “position of words,” and have nothing to do with the “case” concept in English grammar of the same period. Li Jinxi pointed out: “Western grammar is used to regulate changes of word forms (declensition); whereas what I call ‘positions’ is used to probe differences in syntax; though the two resemble each other, their uses differ, and one should clearly distinguish them and must not mix them together.” Quite a few scholars, when criticizing the theory of seven positions, in fact unconsciously had in their minds a permeation of “Western ‘morphological’ grammar,” which violates the logical principle of the “law of identity,” and naturally is not worthy of emulation. The establishment of the seven positions is in fact seemingly complex but actually simple, and is not, as some scholars claim, a term that “can exist but need not exist.” As Liu Danqing points out: “After introducing contemporary linguistics, levels such as argument structure/valency were re-established; in fact, this is, in a certain sense, a return to the intermediary level of ‘positions’… The theory of ‘positions,’ on the one hand, facilitates cases where components of the same position serve different syntactic components, with distinctions between ‘constant’ and ‘variable’; on the other hand, it can also reveal cases where the same syntactic component accommodates components of different positions, likewise with distinctions between constant and variable.” Looking back at today’s modern Chinese teaching, in addition to taking form as the absolute standard, it sometimes also involves semantic agent/patient and the nonequivalence with syntactic structure, but doing so is not only messy and dragged out—worse still, it leaves many students completely confused, which is not conducive to clarifying the internal connection between different expressions of the same sentence meaning, or what Stratificational Grammar calls the “realization relation” discovered beyond syntactic paradigmatic and syntagmatic relations. Moreover, contemporary linguistics generally establishes intermediary levels to clarify certain relations between morphology and syntax; this is not exclusive to non-morphological languages—morphological languages also establish them. This shows that, in exploring intermediary levels, we need to “return to simplicity,” and then continue moving forward.

“Any word: distinguish its category by the sentence; away from the sentence, it has no category,” is Li Jinxi’s famous saying, and also one of the Li-grammar viewpoints that has been questioned the most. The original meaning of this sentence is actually closely related to the theory of seven positions, because the diagramming method is nothing more than a graphical representation of the six major components and seven substantive positions. As for so-called word categories (词品), Xin Zhu clearly states that it refers to word classes “as components assigned within syntax,” while word classes are “classes distinguished from the essential nature of concepts”; that is to say, word classes and word categories belong respectively to lexical category and grammatical category, and the two are not the same. Only by understanding this can we understand that “Any word: distinguish its category by the sentence; away from the sentence, it has no category” is basically tenable in its expression: a word’s grammatical properties must be manifested at the sentence level, otherwise they cannot be distinguished; word classes do exist—they exist in the “most essential” distinctions within human concepts, somewhat similar to prototype theory in the category concept of cognitive linguistics. Structuralism emphasizes syntagmatic relations and holds that a phrase level can also manifest a word’s grammatical properties, which makes some sense; but comparatively, phrases cannot manifest a specific context, and when distinguishing word categories, one cannot better perform disambiguation; for example, “学习文件” (“study documents” / “learning documents”), at the phrase level it cannot be explained clearly. Later Li Jinxi revised his wording, holding that “‘away from the sentence, it has no category’ is incorrect; for example, the formation of compounds basically needs to be based on independent word classes.” But judging from his second later letter to Zhang Wenhuan about the seven positions of entity words—“In 1924, Xin Zhu Guoyu Wenfa already presented that the method of distinguishing Chinese word classes is ‘distinguish classes by the sentence; away from the sentence, there are no classes’”—he seems to have wavered on this, but after wavering, he became steadfast. What is going on here? The author believes that this should be traced to the level of an etymological view. From the perspective of syntactic growth and genesis, so-called phrases and the like are merely differentiations of syntax. In fact, when we speak of the combinational relations of phrases, we refer to relations among syntactic components, so there is also the saying that the structure of Chinese phrases is basically consistent with the structure of sentences. The phrase level originally both is and should be subordinate to the sentence level; when we judge word categories at the phrase level, we actually always have considerations at the syntactic level, which no one can avoid. If not, one cannot explain why some people’s first-glance intuition is that “学习文件” is a predicate-object structure, some intuit it is an “attributive-head structure,” and some are uncertain. In fact, these are all concrete representations of the projection of syntactic-level considerations in the human mind; evidently, each person’s mental embodiment is not the same, resulting in different gestalt perception. Sentences are alive and dynamic; language is also alive and dynamic; thought is also alive and dynamic; hence the sentence-based approach can respond with ease. As for Xu Jialu’s point that Li Jinxi replaced the original “must” and “only then” with “although there is” and “still need,” changing “distinguish categories by the sentence” from the sole standard into an important standard, this fact seems not so important.

Integrating the six major components and seven substantive positions, together with the diagramming method, Li Jinxi obtained the following “characteristics of the national language.” One can say that this understanding of his is profound, integrating considerations across the three planes of pragmatics, syntax, and semantics, with the advantage of controlling complexity with simplicity:

Word positions change with the momentum; when the momentum is heavy, they move forward; moved forward to the sentence-initial, their weight equals that of the subject; once components are delineated, they are comprehensively interrelated, and in principle do not change lightly; though components do not change, word order has shifted, yet meaning still closely fits. Viewing structure thus, only then do rules become settled.

It must be admitted that, although Li Jinxi had very clear principles and a theoretical framework, and had a profound understanding of Chinese grammar, often with unique insights, in the concrete process of operation, in the details of theoretical application, and in the expressions of proposed principles, there are often aspects that cannot fully satisfy people. For example, he almost comprehensively used semantic, pragmatic, syntactic, or formal-and-meaning criteria as the basis for grammatical analysis, often with muddled and ambiguous parts; when speaking of the issue of category conversion under the seven positions, he also has inconsistent statements; (Hua Jianguang, Sun Jianwei) the diagramming method is suspected of being cumbersome, and the general formula for diagramming is overly simple, far from sufficient for use—it only provides a generalized summary of the common patterns of simple sentences, while the construction methods of many more variant simple sentences and of complex sentences are scattered throughout Xin Zhu and are not systematic; the appended notes on the compilation style are trivial and fragmented, “broad but not specialized”; the establishment of the seven positions and the relation between word classes and syntax are not explained sufficiently in theory; the critique of the word-based approach lacks systematic theoretical explanation… Of course, flaws do not conceal merits; in fact, these problems are still very thorny to this day, and one cannot be too demanding of predecessors. Moreover, in terms of the relationship between a scientific system and a disciplinary system, Xin Zhu has already very beautifully achieved the unity of the two, and often has insights that transcend its time, which is astonishing to later generations. Furthermore, these shortcomings are only minor blemishes in the process of concrete theoretical operation, and cannot be used to deny the rationality of the sentence-based thought. On the contrary, I should further discuss and excavate the profound implications behind the sentence-based thought, improve past shortcomings, and achieve present development. This is the proper path of academic progress and the demand of the times.

3 Conclusion

Li Jinxi truly deserves the title of a master linguist; yet we have consciously downplayed the significance of Li’s grammar for modern Chinese grammar, which is one-sided, disproportionate to his academic status, and also unfavorable to the development and progress of grammatical theory and teaching in our country. This paper mainly introduces the background of the emergence of Xin Zhu Guoyu Wenfa, and further explicates the etymological view contained in the sentence-based approach and its application within Xin Zhu Guoyu Wenfa, proving the great significance of the sentence-based thought. This great significance tells us: the sentence-based thought not only conforms to the linguistic realities of our country, but perhaps also has a universal applicability that transcends time and space, with profound cognitive motivation, and its philosophical linguistic implications should not be underestimated. Moreover, a grammar system under the sentence-based approach, whether in terms of its system scale, the weight of its specific content, or the relationship between its disciplinary system and teaching system, may not necessarily lag behind the modern Chinese grammar system—this is worth our reflection. Finally, the author believes that grasping this great significance requires further deep excavation and further promotion by the linguistics community; only thus can we be worthy of the cultivation of our predecessors; only thus can we, on the basis of inheriting our predecessors, surpass them. This is the inevitability of academic progress and the inevitability of history; we should go with the trend, forge ahead, and strive to integrate modern grammar and make it distinctive within the international grammatical community.

Comments