A Study of Sexual Perceptions in China

Disclaimer: This post was originally written in Chinese and translated into English by GPT-5.2.

Introduction

Explanation of the Topic

In ancient China there was the study of punctuation and pausing, teaching people how to segment sentences—within a sentence, a passage, or an article—to make clear where the pauses are and where the meaning lies. Now there is no need for such trouble. Yet in the past there was also once popular a kind of “punctuation study” with a “rather large amount of information”: within a sentence that has only one full stop there could be several different layers of meaning, and each layer was very clear—what is called double entendre comes close to it. For example, “There is a kind of feeling called love” has two ways of reading it, obvious at a glance. “Inquiry-based learning” is exactly this type of topic. However, its hidden meaning is not limited to two layers.

Sex is a very, very big topic. The “sex” of this “research” is in a narrow sense, referring specifically to the social concepts of sex that are universally present. But this is still a very big topic. In the field of sex research, depending on differences in method, one can draw on ethics, psychology, the study of ideas, biology, statistics, history, even international relations, etc.; depending on differences in angle, one can also展开 from sex and politics, society, institutions, culture, economics, geography, etc.—not to mention the many items refined from these methods and angles.

However, this “research,” in the final analysis, is only a kind of “learning.” Since it is learning, that indicates the immaturity of the content; even if it is big and empty, it is not impossible to understand. This kind of learning, though the topic is sensitive—saying what others have not said, what others dare not say, what others cannot say—still, the “spirit of learning” it displays is undoubtedly worthy of commendation.

Of course, what is called sensitive is also relative. In fact, sex research has long ceased to be any big deal. Saying the topic is sensitive should be considered within a specific context. That is to say, if this unprecedented—or perhaps never-to-be-repeated—middle-school student project research of mine is viewed in the specific context of middle-school education, then it is too bold. Actually, anyone who has received even a little sex knowledge or sex education would not find this astonishing, and would even think I write very naively, because after putting down the pen, I have precisely this sigh.

I believe this “research” has the following characteristics: ambitious and far-reaching yet supported by citations; not bound by convention yet striking out on a new path; heterodox yet opening a new trend; a one-sentence hall yet solidly in the right; handled personally yet one against ten; what the crowd deems offensive, yet I go alone.

As for why I locked onto this topic, the reason is simple: entirely because others neither do it nor say it, offering neither constructive contributions nor constructive proposals; the author had no choice but to come as interest leads, as nature leads—unexpectedly, with a clever mouth, I obtained it.

Why Speak of Sex

Although I said it came as interest leads and as nature leads, this interest and sex are not accidental.

Food and sex are of human nature: every day when you eat, drink water, breathe in and out, you are in “food”; every day when the three urgent calls press you to go to the toilet, pull down your pants and relieve yourself, “sex” has been giving you impressions in the dark all along—its effect surpasses advertising. So the issue of sex, or what is called sexuality, you cannot avoid; if you avoid it, it will come looking for you—its barbarity, only politics can rival.

What is called barbarity actually refers to instinct, instinctual impulse. According to Freud’s theory, the fundamental driving force of life is libido, that is to say, what governs you is sexual energy, sexual impulse, and nothing else has “decisiveness”; under the governance of sex, sexual satisfaction in life is divided into six stages, namely the oral stage, the anal stage, the pregenital stage, the latency stage, the postgenital stage, and sexual life①. Sexual satisfaction obtains pleasurable satisfaction by stimulating different positions of erogenous zones, thereby satisfying sexual desire. In other words, crudely speaking, when you feel great, it is actually sexual desire that has been satisfied. Why say this? Because Freud thought the antonym of civilization is instinct; the function of civilization is to repress instinct; and the only instinct that can escape death and cannot be completely killed off is sex—so a person’s life is spent in the contradiction between sexual repression and sexual impulse. This view is indeed biased; for example, there are many unclear and inexplicable places, and there is suspicion of defining sex too broadly; but it also has highlights not without merit: First, it explains the relationship between civilization and instinct—this relationship had in fact already been demonstrated in the book Xunzi②. Their bias lies in not seeing clearly the essence of civilization: mediation, even at the cost of barbarous mediation—repression is also mediation. Second, it fully elevates the status of sex in life and caused the world’s attention to “sex,” bringing wave after wave of discussion and controversy.

Another “not accidental” reason lies in the author’s own interest and the broad masses’ sex interest. Whether interest or sex interest, neither can conceal this reality: their source is society, and they are being teased up earlier and earlier in the hearts of the masses, unable to remain latent—our masses are becoming sexually mature earlier and earlier—of course, this precocity is also widely manifested physiologically. Another reality is: our masses cannot keep up with their own precocity in terms of sex knowledge and sex education. Thus, more and more are sexually repressed or even die of sexual suffocation; more and more erotic jokes, books, and anime; “Aruba” escalating; in private “Have you jerked off yet” increasingly tending to replace “Have you eaten yet”…… And there are those who bring up sex at the drop of a hat; men and women together talking about “Teacher Sora”; those who, upon saying “foundation,” must extend it to the level of “chicken” and then “prostitute”; those who, upon saying pen cap, must associate it with “your cunt” “your condom”; those who, upon saying holiday, think of menstruation; those who, upon saying phonics, think of genitals…….. “sao-nyouth” rather than youth, “big wet chest” rather than big senior brother, “chest weapon” rather than deadly weapon; among gay bros and besties, not a few are homosexual; GV (gay video) more popular than AV; upon seeing photos of partial nudity such as bare arms, cleavage, even male compatriots’ bare upper bodies, they jokingly shout to leave seeds; and there are also obscure internet slang such as comrades, lilies, chrysanthemums, and the Arabic numeral 3…… Social mores are like this—at least the younger generation is already like this—but in fact, so-called adults are no better—at least the younger generation mostly are “transmitting but not creating” “Confucius sages,” while adults are practitioners who both say and do, or even only do and do not say—there are those who hide at home, hide in public offices, or even openly watch porn on buses; there are those who patronize prostitutes, solicit sex, sexually assault young children, female students, female subordinates, send “sister flowers,” even store sex slaves; there are those who fake sodomize and sodomize humans, truly sodomize and sodomize beasts; there are those who go deep into women’s private parts to give psychological treatment and catch ghosts…… This is no longer a matter of a minority or of generalizing from the particular; one can say these are all representative, undeniable, telling facts. But our social mores also make us “impotent” and unable to speak when we talk about sex publicly, so these realities indicate both some progress and some problem. As in modern sex history: sexual awakening has come, but it does not amount to sexual liberation; further sexual enlightenment is still needed③.

Precisely for this reason, as a rational person, I have long deeply felt the importance and necessity of writing about sex. This topic of sex must be straightened out a bit; without straightening it out, how could one be rational?

How to Write and What to Write

I am probably a skeptic; I do not much believe in any essence. I think that essence is often unreliable; the only reliable thing is real phenomena and existence.

There is a phenomenon worth deep thought: those who flaunt essence often decline; those who reveal phenomena often remain evergreen. Strictly speaking, the word essence does not make sense, because essence cannot be explained; and according to essentialists, there is nothing that cannot be explained. To step back, essence is a summary or presupposition (needing no proof) of some eternal phenomenon. That is to say, the “essence” of “essence” is in fact phenomenon. However, this essence is only an explanation of the phenomenon. For the sake of smoothness, explanations often do not hesitate to “selectively express” phenomena by keeping one eye open and one eye shut—is this what is called “essence”? Before long they will blush as they discover their system is outdated and disconnected, yet the phenomena are still unchanged. Since the phenomena are unchanged, then the essence they spoke of is still right, so they brazenly use imagination to continue flaunting essence, with the result being covering up errors and glossing over faults. Materialists also cannot avoid—indeed, are even the most—insincere to the point of idealism; the reason lies here. Here, I would rather reveal. As long as what is revealed can stand, then although explanations vary with a person’s level, they will not differ too far.

Those with self-knowledge never flaunt any essence. Bohr’s famous principle of complementarity profoundly points out that people know one thing at the cost of not knowing certain other things; people can never know everything at the same time④. I think: if it is a phenomenon, it is not accidental. Everyone in the country says we are poor, yet you use a set of ghostly doctrines to achieve spiritual victory, explaining that we are not poor—what kind of essentialism is this? Phenomena are like light, casting sheen on all things; whether through diffuse reflection or specular reflection, they can give the eyes brightness.

In order to strive for a good revelation of phenomena, naturally one needs to grasp the laws of phenomena, ensuring the reliability of the phenomena; otherwise the argument will be unstable. This involves a view of history. In this text, I emphasize two points of my view of history: first, history is not entirely reliable. Second, history is not entirely to be read straightforwardly from books; sometimes it must be read in reverse. These two views of history will be embodied in the writing below.

What I now want to write is mainly to take history as warp, narrating by chapters, merely borrowing the exterior of a paper; in writing, I also take sex as weft, touching lightly like a dragonfly skimming water, adopting the interior of phenomena. The length of each chapter is not limited, adapting to circumstances; the issues brought in are not without selection, using the topic to expound. In short, everything within the warp-and-weft network serves the text; there is no nonsense—those seemingly idle chats are also relevant and justified, handling the heavy as though light. My purpose is only to write about sex through history, especially reflecting, through people of each period, the characteristics of social sexual concepts of that time as different from other periods, telling those who live in the modern era yet—whether big head or little head, brain or dick, metaphysical or physical—cannot keep up with the development of the times, that sex is something everywhere, at all times, nothing more normal.

According to my plan, I will not give the text large-scale discussion. Therefore, under my conclusions, what occupies the主体 is often the process of demonstration, namely the organization and laying-out of phenomena, rather than results.

For the convenience of demonstration and limited by the defects of the author’s knowledge, in demonstration I will often borrow some public opinions that need no further proof. Although not very rigorous, at places where I am clear-minded and firm, I must carefully examine public opinion and strive for rigor.

Descartes’ famous saying “I think, therefore I am” (I think,therefore I am) is often misunderstood and forcibly attached to the idealist theory that “consciousness determines matter”; this is wrong, because its original meaning is “when I am thinking, the only existence I can be certain of is myself.” Therefore he must discard all preconceptions and, from the indisputable proposition “I am” (I am), deduce his philosophical system; this is neither materialist nor idealist. But Descartes’ “universal doubt,” doubting all public opinions, is also wrong, because a person cannot doubt everything at the same time, just as a person cannot know everything at the same time.

I have the spiritual temperament of agnosticism, with unreliable doubts about existence; but I also have the theoretical character of a knowability theorist: phenomena can still explain existence.

Content Overview

When I read sex histories written by foreigners, they talk about European and American countries—there is no China. There are not many works in the field of sex research in China; if there are, most also borrow Western theories to talk about sex and sexual life. In short, there are not many who research and write a Chinese sex history. This causes the author, when writing sex history, to have little reference to speak of. Chinese sex history is not so easy to write; even so, my broad direction still speaks about China, with no harm in mixing in foreign examples as supporting evidence.

History is also a very big topic. Therefore, when writing, I aim to start with the big aspects, with no intention of refusing to let go of small places. Matters in small places are too delicate, too cumbersome, too complex—beyond the author’s ability, and also not what I wish. What the author can do is naturally to set out from literature and history, adopting various views to benefit my own. But if there are those who can see the big from the small, of course those must also be discussed.

Finally, let me state one sentence: the author does not wish to wade into this river of right and wrong; I do not wish, in ignorance, to make value judgments involving sex, because people’s sexual concepts truly have no one who is higher and no one who is lower; they are all merely products of reality. If one really must distinguish who is good and who is bad, like falsification theory, we can only confirm which kind of sexual concept is not good, and cannot prove which kind of sexual concept is correct. Even so, I do not wish to make such judgments consciously.

The following is the content overview:

According to the characteristics of social sexual concepts, I have divided human history since there are traces into three periods: sexual worship in the prehistoric period; openness and conservatism from the Xia dynasty up to before the founding of New China in 1949; and “sexlessness” and “sexuality” from New China to the present.

Sexual Worship

Before prehistoric society formed and the state was built, China, like all peoples of the world, universally worshiped sex; this worship is what is now called “sexual worship.” This worship lasted a long time; even now, our every gesture still bears its shadow. Though the time is remote, we may not necessarily know the origin of this worship (for example, whether because productivity was extremely low at the time, people shifted from worship of reproduction to worship of sex; or because people’s intelligence was not yet opened, psychologically, a sense of worship arose spontaneously from the pleasure produced by sex, or from the mystery of sex), yet one cannot deny the fact of sexual worship.

Openness and Conservatism

When society first formed and the state was already built (below I take the Xia dynasty as the boundary, to distinguish from prehistory), being not far from remote antiquity, the legacy of sexual worship was still very obvious. Manifested in people was the openness of sexual concepts and the openness of social mores—of course, these are said with today’s eyes. This openness also persisted for quite a long time (no settled conclusion, but it certainly existed); compared with ancient Greece, it was not inferior. This perhaps is also where world cultures share “commonality.”

But later, when political power became increasingly centralized and the morality attached to politics became increasingly influential, the degree of sexual openness also became worse with each generation; there may also have been other reasons, such as people’s sense of privacy becoming stronger, etc. But in any case, at this time people’s sexual concepts began to become conservative, and the sense of shame toward sex became increasingly strong. This influence still exists to this day; one cannot say there is no traditional influence. Even so, at the level of the whole society, China historically never had a Western-like age of abstinence; although ritual teaching ate people, it was still not that fierce. But this neither denies the existence of extreme ritualists, nor denies the fact that under the sexual repression of ritual teaching, many victims of ritual teaching were produced. It is only to say that, in general, Chinese people at that time—like later Chinese people—also were not without flexibility in this aspect of sexual concepts; they were not absolutely extreme.

“Sexlessness” and “Sexuality”

Shame toward sex, in the first 30-plus years after the founding of New China, was brought to an extreme in a disguised way, to the point that the entire society ignored sex; sex seemed to have evaporated, and the whole society presented a state of having only politics and no “individuality.” On the one hand, this also came from the influence of traditional factors, but to a large extent it should be attributed to the leadership of the Chinese Communist Party’s left-leaning thought at that time.

After Reform and Opening Up, as a kind of correction of past thinking and concepts, sex slowly began to be no big deal. That is to say, it is in the 30-plus years after this period that, in sharp contrast to the past society, sex could be paid attention to in society. Society did not ignore sex; individuals were also paying attention to sex. Moreover, from this period of political and economic reform, social sexual problems also correspondingly and inevitably appeared.

But we should see that the Chinese Communist Party’s attitude toward sex has always been serious. This seriousness is biased toward the negative. That is to say, once sex is mentioned, in ideology what is usually associated with it is negative things. So, in the era of left-leaning thought and politics-in-command, this negative attitude would bring about society’s ignoring of sex; in the era of correction and seeking truth from facts, gradually, this serious attitude would not avoid certain unavoidable social sexual problems. But in any case, within this attitude, sex generally would not be publicly placed in a position of considerable importance.

Because the division standard is the characteristics of large-scale social phenomena as a whole, at first glance the division standards seem different.

Strictly speaking, in the time of prehistoric sexual worship, society and state did not yet exist—this is different from later. But sexual worship really cannot be said to be unique to prehistory. In fact, sexual worship as a profound worship still exists to this day—this is what has been the same all along. And for example, the conservatism and shame of social sexual concepts still exist quite a lot even now.

Therefore, if one uses a unified standard for comparison over time, there is not much comparability. Even if such comparability exists, it is again exceedingly fine and exceedingly detailed. That is why I said this “research” aims to start from the big place, and does not cling to the small place.

Summary

When writing, the author faced problems of selection and omission; taking and discarding, it became this not-very-standard, perhaps improperly chosen “research.” At the same time, I deeply know my limitations in age, experience, and knowledge, as well as practical considerations; I am still not qualified to point fingers at certain issues, so I leave them aside. There are many imperfect places, which is only natural. But the literary talent and comparatively solid writing style that are revealed within can still withstand examination.

Notes

①This is Freud’s famous theory of personality development, also called the theory of psychosexual stage development. This theory includes the first five stages, that is, these five stages from birth to adulthood (oral stage, anal stage, pregenital stage, latency stage, postgenital stage). His basis is precisely the erogenous zones that can satisfy sexual desire; these erogenous zones are spread all over the human body, and as age develops, the mainstream differs, hence the names. As for after adulthood, naturally one should add a “sexual life” for him. In Malinowski’s Sex and Repression in Savage Society, the author was influenced by Freud and “divides the child’s development into four periods (infancy, early childhood, childhood, adolescence)” (see “Translator’s Preface”), which can be consulted.

②Xunzi · Human Nature Is Evil: “As for what is called nature, it is what Heaven has completed; it cannot be learned, it cannot be worked at. As for ritual and propriety, they are what sages produced; people can learn them and be able, work at them and accomplish them. What cannot be learned and cannot be worked at yet is in people is called nature; what can be learned and be able, can be worked at and be accomplished and is in people is called artifice.” This shows that “nature” is instinct, while civilization is “artifice” (from ‘person’ and ‘do’: what people do is called artifice). Nature and artifice conflict from the beginning, therefore he thought human nature is evil (“human nature is evil; its goodness is artifice”), and the function of the sage lies in “transforming nature and raising artifice; for this he produces ritual and propriety; when ritual and righteousness are produced, they regulate laws and standards.” Also, Correct Naming: “That by which life is so is called nature.” Although Xunzi’s premise in discussing nature is not without nonsense, what he calls “nature and artifice” in fact coincides with “instinct and civilization.”

③Angus McLaren, Twentieth-Century Sexuality: A History, “Introduction”: “…….but the belief that modernization in some way ‘liberated’ sex has proved to be a stubborn idea……. While old forms of constraint have undoubtedly been replaced, new forms of repression have also appeared. Therefore, this book is not a ‘progress’ history.” The author may be called a knowing sexual person indeed!

④The everyday habitual usage of “essence” is different from the “essence” spoken of here. I do not oppose speaking of some essence for reasons of habit and convenience; but to insist that something is essence, either is too ignorant or has ulterior motives. Bohr has the principle of complementarity; not by coincidence, Heisenberg also has an “uncertainty principle,” saying that human knowledge and objective reality differ in substance and cannot be measured precisely. Even as learned as Marx, he had to admit to Engels in person: “All I know is that I am not a Marxist!” His self-knowledge is self-evident.

I. Prehistory: Sexual Worship

Hu Shi, in writing Outline of the History of Chinese Philosophy, broke new ground by cutting off the Three Sovereigns and Five Emperors without discussing them, starting directly from the Spring and Autumn Hundred Schools; later it formed a fashion, and no one talked about the Three Sovereigns and Five Emperors anymore. But I am willing to roughly talk about a brief prehistory, to display my view of history from it, and by the way lay down a tone for the entire historical narrative.

So-called prehistory here generally goes up to the Xia dynasty.

<1> A Brief Prehistory

Human life in remote antiquity is no longer verifiable; the bits and pieces dug out of the ground are obviously not enough to recreate the scene of that time. This remote, blank history can only be patched up by means of conjecture and imagination, from the currently so-called scientific perspective.

What can now provide materials for these conjectures and imaginations is nothing more than three major routes: archaeology, scientific investigation, and reference: archaeology of things underground; scientific investigation of primitive tribes; reference to ancient documents. Although we have good reason to believe in the scientific conjectures and imaginations we make, no one can guarantee them, because even science has not yet probed to the end a series of bizarre yet clue-rich mysteries, such as the existence of phenomena of super-civilizations like the Eighth Continent Mother Continent 10,000 years ago, Atlantis, and the like—let alone the fact that piles of historical relics often instead become obstacles to explaining certain historical facts.

—Time can sometimes explain many things, but at the same time, time also washes away many things so that later they cannot be restored. This is not specifically about prehistoric civilizations. In fact, even when humans have learned to establish a complete archiving mechanism, with differing times and changing events, time and space both changing, how could we restore the truth from history where true and false are hard to distinguish and where there are gains and losses? History is only a documentary of time; within this short documentary, you can find the glimmer of history, but you can never reproduce it. From a philosophical point of view, written history and real history are absolutely not the same, because one is subjective and one is objective, and subjective and objective cannot be completely unified. —

Science, before time, may ultimately be powerless and pale, at least with respect to the past that science can no longer salvage. Therefore, we are left only with scientific conjecture and imagination, as science’s salute to time:

When we discuss history, for convenience and some purpose, we like to segment history and draw lines—for example, the history of the earth can be divided into the Hadean, Archean, Proterozoic, and Phanerozoic; within the Phanerozoic it is divided into several “eras,” within each “era” it is divided into several “periods,” within each “period” it is divided into several “epochs.” But historical segments and boundaries are often unclear, because history is continuous; this kind of division is fixed—divide it larger and it can only be rougher and less accurate. Their basis is merely the achievements of existing archaeology and geological scientific investigation, with the help of scientific analysis; if Heaven has consciousness and underground unfortunately is dug out with some evidence sufficient to refresh these achievements, then history should again be rewritten.

Scientists roughly divide the history of life on earth into the Sinian, Cambrian, all the way to the Jurassic, Cretaceous, Tertiary, Quaternary, but the time ranges of these periods can only be said in broad terms; our existing achievements in archaeology and geological scientific investigation can only support to this point—if one speaks more finely, one can only stare blankly. As for places that archaeology and geological scientific investigation still cannot support, one can only conjecture, imagine, or even dispute and argue. For example, the earliest appearance of ape fossils is 8 million years ago, but the 4 million years from 4 million to 8 million years ago is a blank in human history, until more than 3 million years ago, when human fossils again appear. Concerning that 4 million-year blank, scientists, besides staring blankly, can only propose the aquatic ape hypothesis, namely that humans lived in the sea for those 4 million years. The evidence includes: in the places where ancient apes lived, prehistoric shell middens were found (shell animals living in the deep sea); a series of physiological characteristics of modern humans differ from all terrestrial mammals, yet resemble aquatic beasts①.

Human history is truly too unreliable. When we discuss the history of humanity developing into humans in the modern sense, the mainstream opinion is that humans respectively went through the Paleolithic, Mesolithic, Neolithic; the basis is clear: production tools. But this is not entirely reliable either. Not to mention that geographical differences lead to differences in the degree of human evolution and differences in the time experienced in the Stone Age; just speaking of whether there was a Stone Age is uncertain—many regions cannot find traces of stone tool use; some regions simply have no stone tools that can be used! Like the Eskimos living in polar high-cold regions: before being invaded by civilization, what they used all along were wooden tools, and they had no conditions to use stone tools—and this is precisely not just a special case.

We set aside these unnecessary disputes and speak of reliable things—then sexual worship is a very reliable historical fact.

<2> Sexual Worship

From mythological stories, the progenitors of the Chinese nation Fuxi and Nüwa, brother and sister, committed incest; Japan’s progenitors Izanagi and Izanami, brother and sister, committed incest②; the Western progenitors Adam and Eve, committed incest; in Greek mythology, the earth goddess Gaea and her son Uranus, committed incest; in García Márquez’s allegorical novel One Hundred Years of Solitude, there is incest everywhere; in the myths of many peoples there are records similar to a “Great Flood,” with only the “Noah’s Ark” family surviving the calamity—without incest, how could it work?

From remote ancient relics and existing primitive tribes: in the 8th grotto of the Jianchuan Grottoes in Jianchuan County, Dali Prefecture, Yunnan, there is a female vulva stone carving over one meter tall; in the Wusitai Gully and Table Mountain rock paintings of the Yin Mountains in Inner Mongolia there are many graphic shapes of male and female genitalia; in Tibet there are exaggerated female breasts and vulva; on Dongshan Island, more than 100 li south of Zhangzhou, Fujian, there is a huge vulva stone; the Paiwan people, an indigenous group in central Taiwan, have a conspicuously prominent phallic stone pillar “diao god”; many backward peoples in the world still retain dances and rituals symbolizing sexual intercourse (examples mainly see Liu Dalin’s Illustrated Guide to Chinese Sexual History)

These show that our ancestors had very obvious sexual worship.

In Liu Dalin’s Illustrated Guide to Chinese Sexual History, Chapter 2 “Ancient Sexual Worship” specifies sexual worship as “genital worship, intercourse worship, and fertility worship,” which is very insightful. He gives very rich and detailed examples in the book to explain these three types of sexual worship respectively; one may consult it. Here I casually cite a few examples; the time limits of the examples are not confined to prehistory, nor limited to those cited in the book:

-

Genital worship: there are phallic worship and vulva worship. Phallic symbols mainly symbolize testicles, semen, the whole penis; for example: birds (bird head like glans, bird egg like testicles, egg white like semen, the sprinting power of the black bird comparable to the sprinting power of the glans), snakes, gourds, zu (stone zu, wood zu, jade zu, pottery zu), hu. Vulva symbols: hole-shaped objects (pottery rings, stone rings), jade bi-discs, fish (double fish, like labia; hoping to reproduce like fish!), shell patterns (shell motifs. Early humans chose shells as a general equivalent, not unrelated to sexual worship), flowers (Buddhist scripture: “Vajra Division enters Lotus Division; that is the great bliss affair”; forceful intercourse is called “directly doing the flower heart”; patronizing virgin prostitutes is called “opening the bud.” There is a joke: a widow remarries, people send a couplet: “The flower path once was swept for guests; the thatched gate now begins to open for you,” where “thatched gate” is the vulva; this couplet is a dirty joke.) In ancient times there was a certain woman who wrapped both hands around and used her feet to clamp a tall pillar; someone scolded her for being indecent, but she pointed at the “little dick” and said: “Emperors and generals all come from this!”

-

Intercourse worship. The Helan Mountains rock painting “copulation diagram.” In Kushuigou, Table Mountain, Inner Mongolia, a frog-shaped woman’s lower body is inserted by a phallus. In the Hutubi rock paintings about 75 kilometers southwest of Hutubi County town in Xinjiang’s Tianshan Mountains, there are many rock paintings reflecting sexual intercourse. Among the Yi people of Yunnan, adult men, on festivals, hang a wooden phallus at the waist and dance, reveling in intercourse-like gestures.

-

Fertility worship. Fertility worship objects include frogs (see Mo Yan’s novel Frog, Part Four, Section Two, Paragraph Twenty-Three’s description of frogs), toads, pomegranates, fish; the symbolic meaning is many children. Folk customs of seeking children in various places. Folk legends of “Qilin delivers a son” and “Guanyin delivers a son.” In ancient bridal chambers a basin of jujubes was placed, meaning “may you soon give birth to a noble son.” The ancient admonition “Of the three unfilial acts, having no heir is the greatest.” Pottery figurines shaped like pregnant women.

Examples of sexual worship are extremely widespread— not only not limited to prehistory, also not limited to China—already deeply entering our later customs and habits, language and writing, art and architecture. Here are a few more examples:

-

Customs and habits. Last time online there spread a “breast-groping festival”; later, after confirmation by relevant departments, it was “a rumor,” “completely distorted by some men of letters”—at least such corrupting things have long since not existed now. But we can be sure the breast-groping festival should indeed have existed; that it no longer exists now should also be true. At the beginning of the founding of New China, the state once devoted itself to eliminating some minorities’ custom of “fangliao” (nicely put, relics of matrilineal clan society; bluntly put, chaotic incest), but to this day there are still remnants. Customs and habits always consciously or unconsciously display sexual worship in obvious and hidden ways; this is not strange. Last year the author became a “little uncle-in-law,” and saw family members use an iron kettle to hold pig intestines, with the pig intestines extending to the spout, and on both sides of the spout connected a pair of longan fruits threaded with string—clearly the shape of male genitalia; I asked family members, and indeed it is used to attract a male! In addition, there was another bag of flowers; family members also did not know what it referred to, but from the custom it is so. Yet flowers symbolize the vulva; it should indicate giving birth to a girl.

-

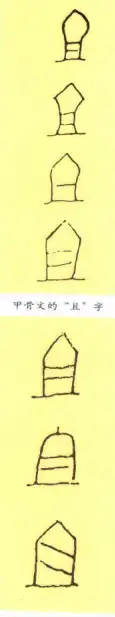

Language and writing. Every country’s “national curse” is suspected of “sexual assault” (see Feng Youlan’s “National Curse” and “Further On ‘National Curse’”). In oracle bone script, “且” and “圭” look like a penis; even in simplified characters, one can intuit it. The left side of “祖” and “祝” is the character “示”; one says it indicates worship, that is worship of the penis—today, ancestor worship of tombstones and ancestral tablets is this imagery; one says it means vulva; one says it is an inverted penis, as if in Wang Xiaobo’s famous poem “walking in silence walking in the sky and the penis hanging upside down.” The ancient seal script of “妣” (pìn) and “也” resembles the labia majora, labia minora, and clitoris. Zhao Shimin’s book Sex, Painful Yet Happy: Dr. Tang’s Sex Psychology Clinic gives new interpretations of the characters “家” and “淫.” Why is there a pig under “home,” not other livestock? Because pigs are prolific. “淫” can be拆 as water, grab (i.e., claw), and ren-tu (壬), where ren-tu is human yin (heaven is yang, earth is yin)—that is, genitalia; the whole character means using the hand to grab the genitalia to make it flow with water, wet (male ejaculation; female full高潮 flowing out Zhang Jingsheng’s “third kind of water” or “Bartholin’s fluid”). This resembles the character “寺.” In ancient China, the “great temple person” referred to eunuchs, because “寺” is from earth and inch: earth indicates genitalia, inch indicates a hand holding a knife to cut; thus “寺” means cutting genitalia. Of course, the “寺” in “great temple person” is passive voice.

- Art and architecture. Pagoda spires and stone pillars—anything尖, and anything concave—are hard to say have no hidden meaning of genitalia③. Last time online there spread a copulating Buddha statue, condemned as indecent; in fact this is rather an elegant matter! Li Ao has written不少 this kind of article, such as “Joyful Buddha,” and also Liu Dalin’s Illustrated Guide to Chinese Sexual History, Chapter 8 “Religion and Sex,” with “Esoteric Buddhism and Joyful Buddha,” all provide sufficient references. Some pottery figurines, stone carvings, woodcuts that deliberately exaggerate genitalia and breasts. In Wang Qingyu’s book Amulets, in the appendix, among the more than one hundred pictures of Khitan amulets, the vast majority have this kind of exaggeration.

<3> Why Sexual Worship

Sexual worship and making love are inseparable; people must make love, and then there is sexual worship—this is beyond doubt.

Humans are different from “beasts.” Beasts have fixed estrus periods; during estrus their genitalia undergo changes such as redness and swelling, thickening, etc.—they must go make love to “reduce inflammation and relieve itching.” Humans’ brains are highly developed; they have no fixed estrus period and can do so “selectively.” But humans are also beasts: humans also have high-incidence periods of springtime yearning, and also have physiological changes similar to beasts. It can be seen that, regressing to the “human beast” of millions of years ago, there would not be much difference; it would likely be like beasts now. From this angle, making love truly is to satisfy psychological pleasure.

According to Liu Dalin’s division method of sexual worship, then when primitive productivity was extremely backward, for survival one had to have sufficient labor power, and the production of labor power could only come from reproduction. To put it popularly: in order to live, you must make love. From recognizing the difference in genitalia, to making love producing new labor power, to linking reproduction with producing new labor power, the ancestors would naturally develop sexual worship characterized by genital worship, intercourse worship, and fertility worship. From this angle, making love truly is because of the level of development of productivity.

Of course, productivity and human psychological mechanisms cannot be discussed separately; that is to say: for survival, people must increase labor power and reproduce through sex and love; at the same time, sex and love is also a matter as the ancients said, “Why is that concave, and I convex? Using convex to test concave, it feels very beautiful and pleasant,” stimulating people again and again. Likewise, if there were no pleasure to urge people to make love, it seems that no matter how high productivity development is, there would still be old virgins; it seems that no matter how high productivity is, it would have nothing to do with the lovemaking of birds and beasts!

Sex is truly a mysterious thing. We can only affirm that sex is instinctual impulse, is a source of creation, can produce pleasure, can make people happy; beyond that, we know nothing. Perhaps this mystery is the fundamental reason for sexual worship, and also the fundamental reason why prehistoric humans worshiped ancestors and heroes, worshiped wind, rain, thunder, and lightning, worshiped birds and beasts, etc. Driven by this mystery, in myth and legend, although humanity’s progenitors all commit incest, when it comes to later sages and holy maidens, these guys are all not born at all; even if they are born, they usually still have some unusual “auspicious signs”! Sexual worship reaching this point can be called transcending into sanctity, godlike and mysterious!

—Do not think that with productivity and science developed to today, sex is no longer mysterious. Do not think that the smarter people are, the less they worship sex. Li Ao counts as an expert in the field of sex research; on Weibo he has public texts of sexual worship:

Forty years ago, in the toilet, Liu Jiachang, while urinating, lowered his head and muttered. He said: “Dick! Everything I suffer, damn it, is for you!” I laughed loudly when I heard it. I said: “Dick is actually a true man. Can bend and can伸, can be soft and can be hard, can use soft-hard together, can be hard within softness. The thing I worship most in my life is this big dick of mine. Although it has brought me many troubles, it is all worth it!”

But perhaps the inscription of the Paiwan “diao god” in central Taiwan is the most plain and true psychological realism of sexual worship; yet aside from that, we still know nothing:

Mighty Diao God, the flower of humankind. By nature gentle, seeing sex then stands. A romantic figure, the root of calamity. Passing on the lineage, without me it will not work. Men and women infertile, please seek this lord. Fitting to enjoy offerings forever, to hang down through ten thousand generations in lasting glory.

Notes

①For example, physiological phenomena such as human tear glands secreting tears to排出 salt, human skin being裸露, humans having thick subcutaneous fat, the position of fetal lanugo in human fetuses, are close to aquatic beasts and are different from all terrestrial mammals. Aquatic beasts refers to aquatic mammals. But strangely, a human embryo at week 8 is extremely similar to a turtle at week 6, a dog at week 6, and a chicken at day 5. Therefore, relying on physiological characteristics to explain certain issues is unreliable. As for prehistoric shell middens, they are also not very reliable. The above discussion benefited greatly from the “Conjecture Series” books published by Chengdu Map Publishing House in 2004, especially Recalling Remote Antiquity, Life演绎, Human Evolution these three books. The examples cited here almost all come from them.

②According to Hao Yong’s You Should Have Read Japan This Way, Chapter 1 “Mythological Age”: the two siblings hold the “Heavenly Jeweled Spear” bestowed by the gods of heaven to stir the “milky sea.” The author says: “‘The Heavenly Jeweled Spear’ symbolizes the male genitalia, while the milky sea into which it is inserted and stirred represents the female genitalia; the whole process can be regarded as an implicit description of reproduction by ancient Japanese.”

③In Illustrated Guide to Chinese Sexual History, the book cites a passage from American historian Weiler’s Sex Worship: “Our towers and spires of various shapes and sizes have all consciously or unconsciously preserved the upright form of the original male genital stone pillars…… In fact, there is no region in the world without stone pillars or towers shaped like male genitalia.” In Liu Dalin’s Illustrations of World Sexual Culture, in the text under the front plates there is such a passage: “Church spires are all symbols of the penis; olive-shaped windows and doors are all symbols of the vulva, that is, the ‘gate of life’.” Laozi, Chapter 6: “The valley spirit never dies; this is called the mysterious female. The gate of the mysterious female is called the root of heaven and earth. It seems to exist continuously; use it without exhaustion.” The “root” and “gate” spoken of in Laozi seem both to refer to genitalia, symbolizing the generation of life, endlessly. Freud’s psychoanalysis, in interpreting dreams, believes that in dreams, protruding things are almost all related to the penis; concave things are all related to the vulva. And as I said in the “Introduction,” every day we receive the advertisement of our own genitalia—how could it not leave a deep impression? It can be seen that genital worship has a long origin and still does not die out today; it can simply be said to have already penetrated into the marrow of humankind, turned into genes passed down, existing in the collective unconscious in the human brain!

II. Ancient China: The Openness and Conservatism of Social Sexual Concepts

Ancient China here generally refers to the history from after the Xia dynasty up to the founding of New China in 1949.The Xia dynasty was the formation of society, the initial founding period of the state; taking it as the beginning is a way to distinguish it from the prehistoric period. From the Xia dynasty to New China spans more than 4,000 years; to people today, it all seems very ancient. Moreover, in my view, modern China, in terms of sexual concepts, seems in the general phenomena not very different from the somewhat older feudal era, so I have included modern China as well. That is to say, the method of periodization here is by no means determined according to the replacement of social systems, although I do not deny the tremendous impact that changes in social systems have on people’s conceptions; we also know that even if the social system changes, in the early stage of that change people’s conceptions to a large extent remain as before, for varying lengths of time—after all, people walk out of the “old society”; the body can remain in the “new society” while the head stays in the “old society.” This is the relative independence of culture.

For example: from after the Opium War to the founding of the Republic of China and then to the founding of New China—in between, although China experienced a “change unseen in a thousand years,” the shock of that change to old, big China was limited; to a large extent, it really was only the signboard that changed while the content remained the same (Lu Xun). For instance, it was only twenty years after the Opium War that China began the Self-Strengthening Movement; even people at the top in China were so conservative—one can imagine the situation of the most numerous small peasants at the bottom (Jiang Tingfu, Modern History of China). Even with the founding of the Republic and the New Culture Movement, when free love and marital autonomy began to be advocated, sexual literature could be published openly, and women began to enter schools and factories and even take charge of state and social affairs, due to the extreme instability of the domestic political situation these still did not, in a short time and on the whole, form a major trend; not without some contemporaries despairing and thinking the Republic was nominal but not real. In short, these “small shoots” as causes should have borne fruit after the founding of New China; although this fruit, for various reasons, was given a new look for quite a long period after the founding of the state, the remote cause had already been planted, and when the time was ripe this fruit would after all still grow out—there was no stopping it. This is the trend presented in recent years.

However, this kind of periodization is of course not rigorous enough; after all, social conceptions are hard to demarcate. This may be a deficiency of my knowledge, and partly for the sake of narrative simplicity so I can be a bit lazy, but for now I can only write it this way. In any case, I am speaking in broad terms; if one were to go into painstaking detail, then in fact almost every topic explored in this “study” could produce a monograph for discussion, which is obviously unnecessary.

During this period, China’s ancient sexual concepts mainly presented two forms: first a period when sexual concepts were relatively open, and later a period when sexual concepts were relatively conservative.

**, A period when sexual concepts were relatively open**

We know that prehistoric people, almost without exception, had very profound sex worship, to the extent that even now this worship cannot be completely erased from people. Then, as a legacy of sex worship, for a long period after the Xia dynasty—when it was not yet very far from prehistory—people’s minds were still very “simple,” and thus they naturally did not treat sex as something shameful. Reflected in people’s understanding and behavior, this was openness in sexual concepts and openness in social atmosphere, although this “openness” was not the same as openness in the strict sense today—because it was merely an unconscious, most normal manifestation.

This “true temperament” of the ancients may make modern people sigh that they cannot measure up; this psychology is like people with bad intentions envying the emperor for having the chance to “travel across more than half of China to sleep with you.” But from the perspective of the whole grand history, this is also perfectly normal. Qian Zhongshu “occasionally flipped through Aesop’s Fables and was prompted” to some “thoughts,” which can serve as an apt annotation here:

“Looking at the whole of history, antiquity corresponds to humanity’s childhood period. At first it is immature; after several thousand hundred years of growth, it gradually reaches modern times. The more ancient the era, the more at the front, the shorter its history; the more the era is at the back, the deeper the experience it has accumulated, the more its age. So we, on the contrary, are the old generation of our grandfathers; the Three Dynasties of high antiquity are, on the contrary, not as long, enduring, and ancient as the modern. In this way, our attitude of believing in and loving antiquity then takes on a new meaning. Our yearning for antiquity does not necessarily mean respect for ancestors; perhaps we simply like children. It is not necessarily for respecting the old; perhaps it is rather selling old age. No old man is willing to admit that he is decayed and stubborn, so we also believe that everything modern, in value and in character, has progressed beyond antiquity.”

Before these words, Chen Hengzhe in her guide to her Western History also said something similar:

“The conduct of adults can by no means be the same as that of children; we have never mocked a child’s suckling because an adult does not suckle. History is the same…… This is the proper attitude for studying history.”

Comparing antiquity to the “children” of the whole of human history is thought-provoking; but to say modern people are “adults” or “old men” is clearly an overestimation—we should admit that the modern is still an immature period, because in a mature period every person is a thoroughly independent individual, not infringing on one another, not needing—or at least not needing—strict moral and political systems to maintain social order and ethical order, able to follow what one desires yet not overstep the bounds. In other words, the modern should be an immature “youth period.” Young people, having received education, on the surface do not dare to point and comment on this minefield of sex; yet privately they prize talking about sex, and as soon as a sensitive word is involved, they shift into the topic of sex. And also because of the education they have received, their understanding of sex is truly worrying, so they are immature.

Shishuo Xinyu records the saying: “The highest forgets feelings; the lowest does not reach feelings; where feelings lie is precisely among our kind!” In fact, “the highest” has no modern sexual troubles; “the lowest” does not have modern sexual troubles; modern sexual troubles are precisely among our kind!

If we view it with this kind of perspective, the people of that time were instead “children.” Children do not understand things and everywhere reveal true temperament, and this is instead the most normal state. Just as poets and philosophers say, truth is there with children.

This is only theory, but the facts do not seem to contradict this theory:

a, The Book of Changes and sex and its influence—before the Zhou dynasty

Sex worship is undoubtedly worldwide. In the “Five Kinds of World Classical Sexology” edited by Han Chuanz i, we can see: Heaven-Born尤物—ancient Greece; The Art of Love—ancient Rome; Kama Sutra—ancient India; Boating on the Sea of Love—ancient India; The Fragrant Garden—ancient Arabia. In these five classic masterpieces, there are discussions of prostitutes, homosexuality, object fetishism, how men please women, how to have sex, what kind of sex is beneficial, women’s sensitive parts…… From this, we can believe that each people in earlier times inevitably left written products of sex worship. Therefore, sex worship is of course also national:

The Book of Changes is publicly recognized as the source of Chinese traditional culture. It was compiled relatively early; judging from various legends, at least by the Zhou dynasty it had already been compiled (according to Liang Qichao, it was in Confucius’s time; see his book Confucius). Later, part of it was lost, mainly leaving the book Zhouyi. As everyone knows, in the realm of Chinese classical studies it occupies a pivotal position. But this strange book with a mysterious tint takes mysterious sex as its warp and weft and expounds the principles of all things and human affairs. In Liu Dalin’s Illustrated Guide to the History of Chinese Sex: Religion and Sex, in “The Mysteries in the Eight Trigrams,” he says: “The yin-yang culture represented by the Book of Changes systematically embodies reproductive culture, and elevates reproductive culture to a new stage. When expounding the philosophical concepts of yin-yang changes, the Book of Changes uses many terms for sexual organs and sexual behavior, profoundly reflecting the content of reproductive culture.” That hits the nail on the head. Then, grasping the “reproductive culture” of the Book of Changes undoubtedly can promote understanding of Chinese sexual concepts:

In the Book of Changes, we can first see the ancients’ emphasis on reproduction; this is what is meant by “The great virtue of Heaven and Earth is called life.”:

With Heaven and Earth, then there are the ten thousand things; with the ten thousand things, then there are male and female; with male and female, then there are husband and wife; with husband and wife, then there are father and son; with father and son, then there are ruler and minister; with ruler and minister, then there are above and below; with above and below, then ritual and righteousness have their arrangement. (Book of Changes, Xu Gua Zhuan) Heaven and Earth’s union, the ten thousand things transform and become rich; male and female combine essence, the ten thousand things transform and are born. (Xi Ci Zhuan) Heaven and Earth respond, and the ten thousand things transform and are born. (Xian) Clouds move and rain is bestowed; the myriad things take form. (Qian) Returning Maiden is the great meaning of Heaven and Earth. If Heaven and Earth do not unite, the ten thousand things do not arise. Returning Maiden is the beginning and end of humans. (Gui Mei. Gui Mei means marrying off a daughter.) Male and female being correct is the great meaning of Heaven and Earth. (Jia Ren) Heaven and Earth unite: Tai. (Tai) Heaven and Earth do not unite: Pi. (Pi. Later, the “Pi” and “Tai” in “When Pi reaches its extreme, Tai comes” originate from this, so Pi is a bad thing and Tai is a good thing. The standard is whether there is union or not!)

Reproduction has since ancient times been an important link in Chinese culture; the best example is linking whether one has children with whether one is filial—the so-called “Among the three unfilial acts, having no heir is the greatest.” Reproduction occupies such a large position in the Book of Changes; isn’t it appropriate to say it represents “reproductive culture”? But the reproduction mentioned in the Book of Changes is not like later times, avoiding sex as taboo; for example, it uses “clouds move and rain is bestowed,” “respond,” “unite,” “combine essence” to describe the state of sexual intercourse. And sexual intercourse (or reproduction) ranks very high, with very high status, on par with the “ten thousand things,” counting as the “great meaning of Heaven and Earth,” so what even are “ritual and righteousness”!

Reproduction and sex cannot be separated. Taking reproduction as the starting point, then naturally sex becomes the fulcrum. In the Xi Ci Zhuan, the Book of Changes plainly writes:

The Master said: “Qian and Kun—are they not the gate of the Changes?” Qian is a yang thing; Kun is a yin thing. Yin and yang unite in virtue, and the hard and soft have form. With this, one embodies the compositions of Heaven and Earth, and connects to the virtues of the spirits and brilliance.

Qian is six yang lines arranged from top to bottom, Kun is six yin lines arranged from top to bottom—clearly symbols of male and female genitalia (yang thing, yin thing)! As for the remaining sixty-four hexagrams, they are merely permutations and combinations of yang lines and yin lines, equivalent to speaking of matters by borrowing sex in a veiled way. In 1923, Qian Xuantong said: “I think the original Yi trigrams were things of genital worship; the Qian and Kun trigrams are precisely the marks of the genitalia of the two sexes.” In 1927 Zhou Yutong, 1928 Guo Moruo, and 1958 Li Ao (see Li Ao, Research on Chinese Sex, Part One) all published the same view. Among them, Guo Moruo said: “In the roots of the eight trigrams we can very clearly see remnants of ancient genital worship. A single line depicts the male organ; split into two depicts the female vulva; thus from this develop the concepts of male and female, father and mother, yin and yang, hard and soft, Heaven and Earth. The ancients’ numerical concept took three as the greatest, three as the most mysterious; from one yin and one yang, a line interwoven becomes three, and it just so can yield eight different forms.” (If each hexagram contains six lines, then permutations and combinations can yield sixty-four different forms.) This sentence can obtain theoretical support from Laozi, Chapter 42 as well: “The Dao gives birth to one; one gives birth to two; two gives birth to three; three gives birth to the ten thousand things.” How does “three” give birth to the ten thousand things? It turns out this “three” denotes the combination of a yang line and a yin line, namely the coupling of a yang thing and a yin thing, hence “three gives birth to the ten thousand things”! So according to today’s joke, one plus one really is three!

From exalting reproduction to speaking of affairs by borrowing sex is similar to shifting from reproduction worship to sex worship, and accords with the laws of human cognition.

From the Book of Changes, we can also find evidence of this speaking of affairs by borrowing sex. Besides the words yin and yang, other high-frequency words in the Book of Changes include hard and soft. As the name suggests, hard and soft belong respectively to yang and yin, and are symbolic objects of male and female genitalia. When we see “Hard and soft begin to unite, and difficulty is born” (Tun), we can associate it with using the pain during sex to explain the principle that good things arise from crisis; and in Sui “the hard comes and is below the soft,” in Gu “the hard is above and the soft below”—isn’t this plainly speaking of affairs in terms of sexual positions? In the 61st hexagram Xian, it even more plainly describes the foreplay of sexual intercourse:

“Xian means response. The soft rises and the hard descends; the two qi respond and join with each other; still yet delighted; the man below the woman (note “below”), thus ‘smooth, beneficial to rectitude; taking a woman is auspicious’ (marrying a woman is very auspicious.)” “Responding at the great toe (touch her toes), responding at the calf (touch her lower leg), responding at the thigh, responding at the back, responding at the cheeks and tongue (kiss her mouth, face, tongue).”

Other instances of speaking of affairs by borrowing sex include:

Though yin has beauty, it contains it and follows the king’s affairs, not daring to accomplish on its own. This is the way of Earth, the way of the wife, the way of the minister; the way of Earth has no accomplishment yet replaces with completion. (Kun. Meaning: Although yin is beautiful and has always had great effect, it does not claim credit; isn’t this what the wife’s way and minister’s way are like!)

It can be seen that speaking of affairs by borrowing sex is very much part of Chinese traditional culture! Or, the so-called “reproductive culture” is an important component of Chinese traditional culture!

As everyone knows, the Book of Changes was by no means written by one person, but rather gathers the wisdom of times before the Zhou dynasty, and is highly representative. This reproductive culture of the Book of Changes easily brings to mind the female shamans of the Yin-Shang, and Yin-Shang female shamans are usually associated with sacred prostitutes—sex worship with religious coloration①. By referencing the two together, we can somewhat unravel the mysterious coloration, with sex as warp and weft, represented by the Book of Changes.

As everyone knows, this reproductive culture profoundly influenced later culture and conceptions; therefore, later Chinese sexual concepts all contain a considerable openness, and this is not unrelated to it. Moreover, from the Book of Changes also arose yin-yang studies; from yin-yang theory also arose the ancient theory of bedroom arts, which is equivalent to the ancients’ sex education reader—thus we can see its profound influence on Chinese sexual concepts. In addition, the folk superstitions and Chinese medicine that still exist today cannot be said to be without this influence.

This influence is also expressed in the strange-recording novels and notebooks of successive dynasties. For example, in some bizarre stories of In Search of the Supernatural, whenever there are stories of people turning into animals or animals turning into people, it is said to be an omen of political upheaval, and the Book of Changes is used as the theoretical basis. The culmination of this influence is none other than Strange Tales from a Chinese Studio.

Beyond this, Confucius also rated the Book of Changes very highly; he said: “Give me a few more years; at fifty to study the Changes, I may be without great faults.” Records of the Grand Historian also records that Confucius’s leather thongs were broken three times, the result of diligently studying the Changes without fatigue. When Dong Zhongshu promoted “banishing the hundred schools and honoring Confucianism alone,” yin-yang studies were merged into Confucianism. Thus Confucianism carries the coloration of yin-yang studies; and Confucianism is an important component of traditional culture, so the whole of Chinese traditional culture also carries the coloration of yin-yang studies.

Moreover, this influence has long since “gone out,” showing signs of being carried forward and developed by others; for example, a decade or two ago the Japanese writer Baku Yumemakura became famous with several volumes of Onmyoji②.

In short, from sex worship and then speaking of affairs by borrowing sex to the self-contained system of yin-yang studies, traces of sex worship began to be gradually concealed, but its essence is truly sex worship, representing open sexual concepts.

b, From the Book of Documents to the Book of Songs—before the Spring and Autumn period

In Investiture of the Gods, descriptions of the Forest of Meat and Pool of Wine (the “meat” includes human flesh) are used to depict the tyranny and licentiousness of Jie and Zhou. In fact, this “licentiousness,” as the social atmosphere of the time, is also possible.

The Book of Documents, Instructions of Yi records: “Dare there be constant dancing in the palace, drunken singing in the chambers—this is called the shamanic wind. Dare there be devotion to goods and beauty, constancy in roaming and hunting—this is called the licentious wind. Dare there be insulting holy words, opposing the loyal and upright, keeping far from elder virtue, being close to stubborn boys (that is homosexuality; China has always been very tolerant of this)—this is called the chaotic wind.” It can be seen that the social atmosphere at the time, in terms of sexual concepts, was quite open and even “licentious.” Of course, this passage is also not credible. Because the Book of Documents itself has been accused of being a forgery, and that passage in particular has been said to be fabricated nonsense. In short, time is too remote and no one can say clearly. However, comparing the depiction in the ancient Greek book Heaven-Born尤物 of similarly “licentious” social atmosphere at that time (likewise many brothels, casual hookups, homosexuality not prohibited), I think that passage, even if fabricated, should still reflect the social atmosphere of the time.

But even if forged, its time was only the Han dynasty; from “After Cheng Tang died, in the first year of Taijia” it was only a bit more than a thousand years away (social progress at that time was not as fast as now; a thousand years is not very long), so it has some credibility. Taking a step back, even if that “licentious” social atmosphere was not of the Xia dynasty, it should still be a reflection of the early Han dynasty (the period when the forged text was completed). Moreover, from the dialogue between King Xuan of Qi and Mencius in the Warring States period we can see: besides King Xuan of Qi liking goods and lusting after sex, the Zhou dynasty likewise had “Gong Liu liked goods” and “Tai Wang lusted after sex”; evidence is recorded in Book of Songs, Daya, Mian, and Mencius only said it was fine, as long as one could share the same likes with the people (Mencius, King Hui of Liang II).

The Book of Songs indeed has much evidence in this regard. The Book of Songs is our country’s earliest poetry collection, collecting hundreds upon hundreds of poems from about five hundred years from the early Western Zhou to the mid–Spring and Autumn period; it is said that Confucius with a sweep of his brush deleted several hundred, leaving the existing 305 poems. These poems include those made by the people—these are the “Airs”; and those made by officials—the “Elegance” and “Hymns.” (People like Deng Zhenduo do not agree with this division; see History of Chinese Literature (Volume 1), but he is somewhat hair-splitting.) I have not studied the Book of Songs in depth, so it is hard to say much; I cannot, like Mencius, see from the Daya that official figures lusted after sex and liked goods. But looking at the folk poems, the “Airs,” we discover that the so-called “licentious wind” and “chaotic wind” have their source. And because the Book of Songs, like the Book of Changes, occupies an important block in Chinese traditional culture, it is necessary to “belabor” it, thereby taking a look at the social atmosphere of the time.

Love is a major theme of these folk songs, and love and sex are inseparable, like Foucault’s so-called relationship between sex and politics—two sides of the same coin. From these love poems, the sexual concepts of the people of the time were still open, a very natural feeling. This openness means that it had not yet been strangled by moral preaching and the like and become conservative.

Here, we can see gentlemen unable to sleep for “the modest and good lady,” “that one I long for,” fantasizing all night; we can see ladies, when they “have seen the gentleman,” so happy like a riot of blossoms, and when they have “not seen the gentleman,” so sad that they wither into last year’s flowers or become as thin as a chrysanthemum. We can see how lovesick men and resentful women think of “being good forever,” “holding hands and growing old together,” how they call out “It’s getting late! It’s getting late! Why don’t you return?” while waiting for their other half amid dew and mud, how they swear, “If you don’t take me, you’ll regret it later,” how they complain, “The woman is not at fault,” but the gentleman “changes his virtue two or three times,” how they lament, with things no longer the same and people no longer there, “In the past when I went, the willows were lush; now when I come back, the rain and snow fall thick.” Of course, these are more negative forms of love, but this negativity is a naturally arising, perfectly normal emotion.

At the same time, we can also see more positive male-female pleasure and love—for example scolding bratty boys, flirting, and trysts—quite contrary to ritual teachings; it can be seen that society at the time was still very good, what moralists call the very ancientness of human hearts. A few examples:

-

Scolding bratty boys. (Airs of Yong, Crafty Boy): “That crafty boy, he does not speak with me. Because of you, I cannot eat. That crafty boy, he does not eat with me. Because of you, I cannot rest.” (Loose translation: You brat! You won’t talk to me, so I can’t eat! You brat! You won’t eat with me, so I can’t have peace!) (Airs of Yong, Lifting the Skirt): “If you would think of me, lift your skirt and ford the Zhen. If you do not think of me, are there no other men? The mad boy is mad indeed! If you would think of me, lift your skirt and ford the Wei. If you do not think of me, are there no other men? The mad boy is mad indeed!” (Loose translation: If you love me, then cross the river over here—hmph; if you don’t like me, do you think no one loves me? You brat!) (Interestingly, “The mad boy is mad indeed” has been punctuated by Li Ao and others as “The mad boy is mad, qie,” with qie translated by him as “cock,” as vulgar language used when cursing, not a simple sentence-final particle. Some accept this punctuation; but some translate qie as meaning “to hell with you.” Others think crafty boy and mad boy refer to same-sex sexual partners; the Chinese have always been quite open about this.)

-

Flirting. (Shao Nan, In the Wild There Is a Dead Musk Deer): “In the wild there is a dead musk deer; white cogon grass wraps it. There is a girl with spring in her heart; a fine man tempts her. In the woods there is rough brush; in the wild there is a dead deer. White cogon grass tied in bundles; the girl is like jade. Slowly and gently undress! Don’t touch my sash! Don’t let the dog bark!” (Loose translation from Baidu Baike: In the wild a fragrant musk deer lies dead; wrapped in white cogon grass it looks proper. A maiden’s heart is full of spring; a handsome man skillfully entices, feelings rise. In the woods the brush is ignored; in the wild the dead deer is still treated with ceremony. Wrapped in white cogon grass and buried; the maiden is like jade and yearns for you. Slowly shedding skirt and robe—what is it you seek? Don’t touch my waistband, please. Don’t let the dog keep barking; the maiden will follow you for life.)

-

Trysts. (Bei Feng, Quiet Girl): “Quiet girl, how fair; she waits for me at the corner of the wall. She hides and cannot be seen; I scratch my head and pace. Quiet girl, how lovely; she gives me a vermilion tube. The vermilion tube is bright; I delight in your beauty. From the pasture she brings back a tender reed; truly beautiful and uncommon. Not that you make it beautiful; it is the gift of the beauty.” (General meaning: A quiet, beautiful girl asks me to meet at the corner of the city wall, but then hides so I can’t see her, making me scratch my head, pacing uncertainly. She gives me a vermilion tube, and also gives me newly sprouted grass from the wild, brimming with affection.) (Airs of Yong, Jiang Zhongzi): “O Zhongzi, do not climb over my neighborhood, do not break my goji trees. How dare I love you? I fear my parents. Zhong is indeed to be cherished; my parents’ words are also to be feared. O Zhongzi, do not climb over my wall, do not break my mulberry trees. How dare I love you? I fear my elder brothers. Zhong is indeed to be cherished; my brothers’ words are also to be feared. O Zhongzi, do not climb over my garden, do not break my sandalwood trees. How dare I love you? I fear the many words of people. Zhong is indeed to be cherished; the many words of people are also to be feared.” (General meaning: Zhongzi, Zhongzi, don’t climb over the wall to come here; there will be so much gossip—people’s words are frightening.)

Confucius’s evaluation of the Book of Songs as “thought without depravity,” “joy but not licentious, sorrow but not injurious” is precisely an annotation to the openness of sexual concepts at the time.

c, After the Book of Songs—after the Spring and Autumn period

Besides the Book of Songs, in many literary works and historical materials we can see that the openness of sexual concepts in ancient China continued for quite a long time. The following examples are all somewhat representative; they can reflect the openness of sexual concepts at the time, or at least a lack of resistance to sex and lack of shame, clearly different from later times:

-

The book Laozi contains terms such as “primal female,” “mysterious female,” “valley spirit,” “gate,” “root,” and the like; it contains reasoning drawn from the phenomenon that an infant does not yet understand what intercourse is, yet the little penis will naturally erect (“Not yet knowing the union of male and female, yet it stands firm—this is the utmost of essence”); it contains lines like “Within it there is essence; its essence is very real,” “The ten thousand things bear yin and embrace yang,” etc. In fact, similar to the Book of Changes, it carries the coloration of “yin-yang culture.”

-

Even the moralists represented by Confucius never slandered sex as something filthy and unbearable—what’s more, Confucius is rumored to be the product of a wild union (this claim is refuted by Kong Qingdong; see his article describing his own genealogy). In the Confucian understanding, sex is only something a gentleman must not indulge in. Besides, they likewise regard reproduction and human relations as extremely important matters. For example, Confucius would praise the simplicity of male-female relations in the Book of Songs, and would also say words with the coloration of Platonic spiritual love (“The flowers of the tangdi tree, how they lean and turn. How could I not think of you? Only that your home is far.” The Master said: “If one has not thought of it—how far can it be?”).

-

The table of contents of In Search of the Supernatural: Xuanchao and a goddess become husband and wife; a woman transforms into a man; three men jointly marry one woman; a man transforms into a woman and gives birth; changes in men’s and women’s clothing; a man transforms into a woman; men’s and women’s shoes; one body with male and female in one; a woman transforms into a man but not completely; Ren Qiao’s wife gives birth to conjoined female infants; a woman has a vulva in her belly or on her head; a woman transforms into a silkworm; Huang’s mother transforms into a giant turtle; men and women unite after death; Lu Chong’s hidden marriage; a giant turtle transforms into a wife…… Someone who doesn’t know and sees these titles might think they are modern stories! And then look at the table of contents of Shishuo Xinyu: valuing the worthy and changing one’s lust; Prime Minister Wang makes female entertainers; Ruan Ji bids farewell to his sister-in-law; Ruan drunk with the neighbor’s wife; Wang Hun and wife joke and laugh; Shi Chong drinks and beheads a beauty; Shi Chong sets maidservants and fragrance in the toilet; Wang Anfeng and wife call each other “qingqing”; Jia Chong’s daughter secretly has an affair with Han Shou…… It even specially sets aside a chapter, “Worthy Ladies, Nineteen,” devoted to stories of these extraordinary women. It can be seen that by the Northern and Southern Dynasties, we were still open about sex, or at least did not avoid speaking of it. (Book from Yuelu Publishing House, punctuated and edited by Qian Zhenmin)

-

In Strategies of the Warring States, Strategies of Han, the Queen Dowager Xuan of Qin uses her own sexual experience to reason with a foreign envoy; in the Han dynasty the earliest spring-palace paintings began to circulate; Liu Bei’s ancestor, Prince Jing of Zhongshan Liu Sheng, designed the earliest extant sex tool in China, and later sex tools emerged one after another; Cao Cao’s will includes “After I am gone for ten thousand years, you all should remarry”; Northern Wei Code: “Men and women who associate not according to ritual all die”; when Wu Zetian’s ministers urged her to “favor” men less, she actually rewarded him; in the Tang dynasty one could openly discuss sexual techniques and sexual literature; Tang Code • Household and Marriage stipulated: if children, without obtaining parents’ consent, had already established a marital relationship, the law recognized it; only minors who did not obey their elders were counted as violating the law; in the Song dynasty one could openly hold women’s nude wrestling (for this point about the Song, see Ge Zhaoguang, “Intellectual History: Doing Both Addition and Subtraction,” Reading magazine, 2003 Issue 1)

d, Summary

From the above, the early openness of sexual concepts, whether in theory or in historical facts, accords with actual circumstances. It is just that from these materials alone, we still cannot see when this openness gradually tended toward conservatism. There is currently no conclusion in academia either—some say as late as the Tang dynasty, some say as late as the Song dynasty; each has its reasons, and opinions differ.